Swiss genome of the 1918 influenza virus reconstructed

Researchers from the universities of Basel and Zurich have used a historical specimen from University of Zurich's Medical Collection to decode the genome of the virus responsible for the 1918 to 1920 influenza pandemic in Switzerland. The genetic material of the virus reveals that it had already developed key adaptations to humans at the outset of what became the deadliest influenza pandemic in history.

14 July 2025

New viral epidemics pose a major challenge to public health and society. Understanding how viruses evolve and learning from past pandemics are crucial for developing targeted countermeasures. The so-called Spanish flu of 1918 to 1920 was one of the most devastating pandemics in history, claiming some 20 to 100 million lives worldwide. And yet, until now, little has been known about how that influenza virus mutated and adapted over the course of the pandemic.

An international research team led by Verena Schünemann, a paleogeneticist and professor of archaeological science at the University of Basel (formerly at the University of Zurich) has now reconstructed the first Swiss genome of the influenza virus responsible for the pandemic of 1918 to 1920. For their study, the researchers used a more than 100-year-old virus taken from a formalin-fixed wet specimen sample in the Medical Collection of the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Zurich. The virus came from an 18-year-old patient from Zurich who had died during the first wave of the pandemic in Switzerland and underwent autopsy in July 1918.

Three key adaptations in Swiss virus genome

“This is the first time we’ve had access to an influenza genome from the 1918 to 1920 pandemic in Switzerland. It opens up new insights into the dynamics of how the virus adapted in Europe at the start of the pandemic,” says last author Verena Schünemann. By comparing the Swiss genome with the few influenza virus genomes previously published from Germany and North America, the researchers were able to show that the Swiss strain already carried three key adaptations to humans that would persist in the virus population until the end of the pandemic.

Two of these mutations made the virus more resistant to an antiviral component in the human immune system – an important barrier against the transmissions of avian-like flu viruses from animals to humans. The third mutation concerned a protein in the virus’s membrane that improved its ability to bind to receptors in human cells, making the virus more resilient and more infectious.

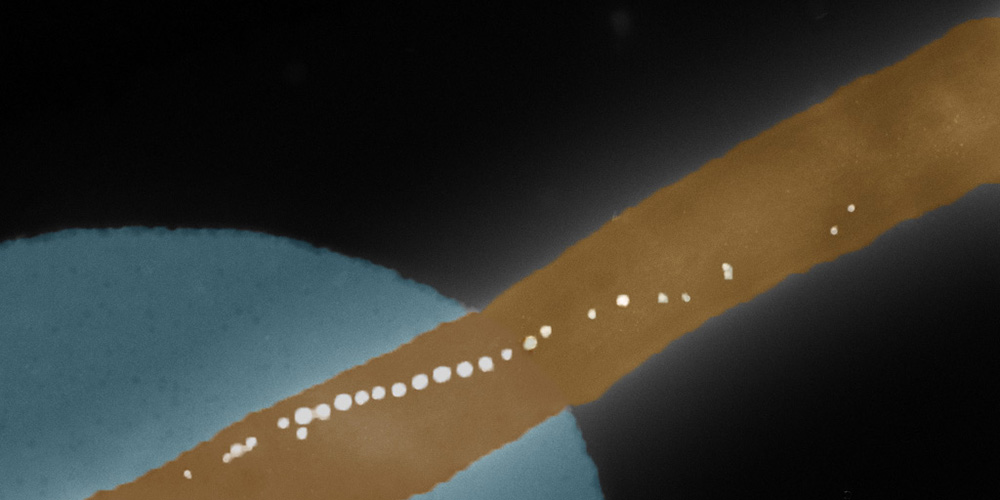

Unlike adenoviruses, which cause common colds and are made up of stable DNA, influenza viruses carry their genetic information in the form of RNA, which degrades much faster. “Ancient RNA is only preserved over long periods under very specific conditions. That’s why we developed a new method to improve our ability to recover ancient RNA fragments from such specimens,” says Christian Urban, the study’s first author from the University of Zurich. This new method can now be used to reconstruct further genomes of ancient RNA viruses and enables researchers to verify the authenticity of the recovered RNA fragments.

Lessons for the future

For their study, the researchers worked hand in hand with University of Zurichs’s Medical Collection and the Berlin Museum of Medical History of the Charité University Hospital. “Medical collections are an invaluable archive for reconstructing ancient RNA virus genomes. However, the potential of these specimens remains underused,” says Frank Rühli, co-author of the study and head of the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Zurich.

The researchers believe the results of their study will prove particularly important when it comes to tackling future pandemics. “A better understanding of the dynamics of how viruses adapt to humans during a pandemic over a long period of time enables us to develop models for future pandemics,” Verena Schünemann says. “Thanks to our interdisciplinary approach that combines historico-epidemiological and genetic transmission patterns, we can establish an evidence-based foundation for calculations,” adds Kaspar Staub, co-author from the University of Zurich. This will require further reconstructions of virus genomes as well as in-depth analyses that include longer intervals.

Original publication

Christian Urban et al.

An ancient influenza genome from Switzerland allows deeper insights into host adaptation during the 1918 flu pandemic in Europe.

BMC Biology (2025). doi: 10.1186/s12915-025-02282-z