Nietzsche is dead – but still lives on

August 25 marks the 125th anniversary of the death of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who was professor at the University of Basel from 1869 to 1879. In this interview, literary scholar Professor Hubert Thüring discusses the relevance of Nietzsche's writings and their continued importance today.

18 August 2025 | Noëmi Kern

Mr. Thüring, why should we still engage with Friedrich Nietzsche today?

For one thing, the way we think is more strongly influenced by him than we are aware, although this influence has faded. For another, there are things Nietzsche can still teach you about directly or which you can investigate through his work, such as the way he writes. In literary terms, he has a lot to offer: hardly any other author I know writes with such color, variety, wit and, at the same time, insight. Nietzsche was a great writer and stylist, and he’s fun to read. You don’t have to tackle him with the idea that you need to understand everything right away and then use his ideas to make the world a better place. After all, he didn’t see himself as someone who would make the world a better place, but first and foremost as a critic and also as a philosopher pointing the direction in which we could go.

Can you give us an example?

I’d suggest Nietzsche’s philosophy of perspectivism, which is more relevant today than ever as society becomes increasingly polarized. Nietzsche would have described it as a form of integrity to want to think about the counter-perspective with the same consistency as about the things you yourself consider urgent or imperative. Nietzsche is also worth looking at when it comes to the general understanding of science: he understood it as something dynamic, constantly changing and therefore oriented not toward truth in an absolute sense, but toward truthfulness. Scientists say that they believe something to be true – but this is not a definitive or fixed truth. This idea enables us to better understand the COVID-19 pandemic: the measures were constantly changing because something new had been discovered about the virus.

How did you first come into contact with Nietzsche?

That was here at the university, because some of my fellow students were attending a proseminar on Zarathustra (four books, 1883–85). Then I heard that the Nietzsche Colloquium was taking place in Sils Maria, and I went there practically without any experience of reading Nietzsche.

You’ve made up for that by now. What is it about the texts that appeals to you?

At first, I read Nietzsche with a very text-oriented approach, with a view to rhetoric and stylistics. My favorites then became particularly his moral-critical, historical-critical writings The Gay Science (Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, 1882/1887) and On the Genealogy of Morality (Zur Genealogie der Moral, 1887). I was less concerned with his aesthetic and poetic works: Zarathustra is too missionary for me, although the character always denies it, but I think the Dionysus-Dithyrambs (Dionysus-Dithyramben, 1888) is one of the greatest poetic works of German literature. I have always rejected gestures of veneration in relation to Nietzsche – just as he did. In Ecce Homo (1888), he wrote that he did not need believers, but readers.

However, he did not achieve this as he would have liked …

Nietzsche’s great tragedy was indeed that he was not properly perceived or understood. He repeatedly addressed this issue with questions that were more than just rhetorical: “Do people really understand me?” He realized that he overwhelmed a general readership.

And yet today he is considered a great philosopher and thinker. What is the fascination of Nietzsche all about?

Generally speaking, it’s the famous and sometimes infamous catchphrases of the “Übermensch,” the “will to power,” the “eternal return of the same,” and “God is dead” that we still know today. I believe that his tragic life also had a powerful effect. I am particularly fascinated by his critique of the mechanisms of power and the production of knowledge. I’m always coming across new situations where I think it helps to have read Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality in order to analyze power plays and power situations.

“God is dead” is probably Nietzsche’s best-known expression. What does he mean by that?

This sentence appears in one of his most interesting aphorisms (The Gay Science, § 125), because it is also literarily brilliant. “The Great Man” (Der tolle Mensch) is an anecdote – a medium in which the Cynic philosophers conveyed life’s wisdom. It is not about aggression in the sense of “Kill God!” or “God is dead and that’s good.” Instead, he observes that we’re the ones who killed God. The question is then rather: what are the consequences of this? Here, Nietzsche’s primary concern is not overcoming something, but diagnosing a state of suspension: what happens if we lose or radically change our fundamental cultural references that are anchored in the idea of God? Nietzsche was of the opinion that what constitutes a society has to be thought about and analyzed from the perspective of the respective historical conditions of knowledge and power. So we were not always what we are today, but we have become that way. And you can only change what you have become.

Nietzsche works a lot with questions. Why is that?

For him, there are two kinds of philosophy, and that is also connected with his tragedy. There is the philosopher as a historian who analyzes things and says how they have become. The other, real philosopher says what needs to be done. Nietzsche thought that he embodied both.

But it is evident in his work that he finds it difficult to get out of the critical perspective and then actually say which way things should go. There are no Nietzsche’s Ten Commandments – at least, not ones that I would say could get us anywhere today.

He also dealt extensively with the climate and the weather – certainly because he himself was affected by it...

Basel is one of the warmer and more humid towns in Switzerland, and that took its toll on him. In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche writes that what constitutes life is not the great ideas, that is, concepts such as God, soul, virtue, sin, the afterlife, truth or eternal life. In his opinion, nutrition, environment, climate, relaxation and “selfishness” in the sense of one’s relationship to oneself are more important, which can certainly also be interpreted in connection with his suffering and illnesses. And as early as in The Gay Science (§ 7), he writes that the most interesting aspect of what constitutes man and life has not yet been researched. Among other things, he asks: “Are we aware of the moral effects of food? Is there a philosophy of nutrition?”

This is evocative of today’s countless nutrition blogs and guides.

Absolutely. Nietzsche saw the circumstances of life as determining factors for how our lives are structured – especially the relationship between health and sickness. He was one of the first to say that no one was completely healthy or completely sick, but that there were only degrees between health and sickness. Health is therefore something that the organism has to create again and again – it is a constant dynamic process. This view of Nietzsche’s is one that we are currently confronted with.

What do you wish for Nietzsche and his work?

In my view, it is important not to antiquate or monumentalize Nietzsche. My greatest concern is for people not to view his works as holy writings and not to allow themselves to be misled by the great sayings mentioned above, which he himself always minimized. Exaggerating him with his own misunderstood catchphrases does not do justice to him or his view of what life is about. Rather, I’d like people to have a relaxed relationship with his thought and writing, and to take a critical and productive approach to resolving these catchphrases with regard to the present. Nietzsche is a historical thinker who can be updated very well. Incidentally, this also applies to the knowledge of antiquity, which Nietzsche himself, as a classical scholar from Basel, updated and which is in danger of being lost with the abolition of Greek as a secondary school subject under discussion.

About the publication project

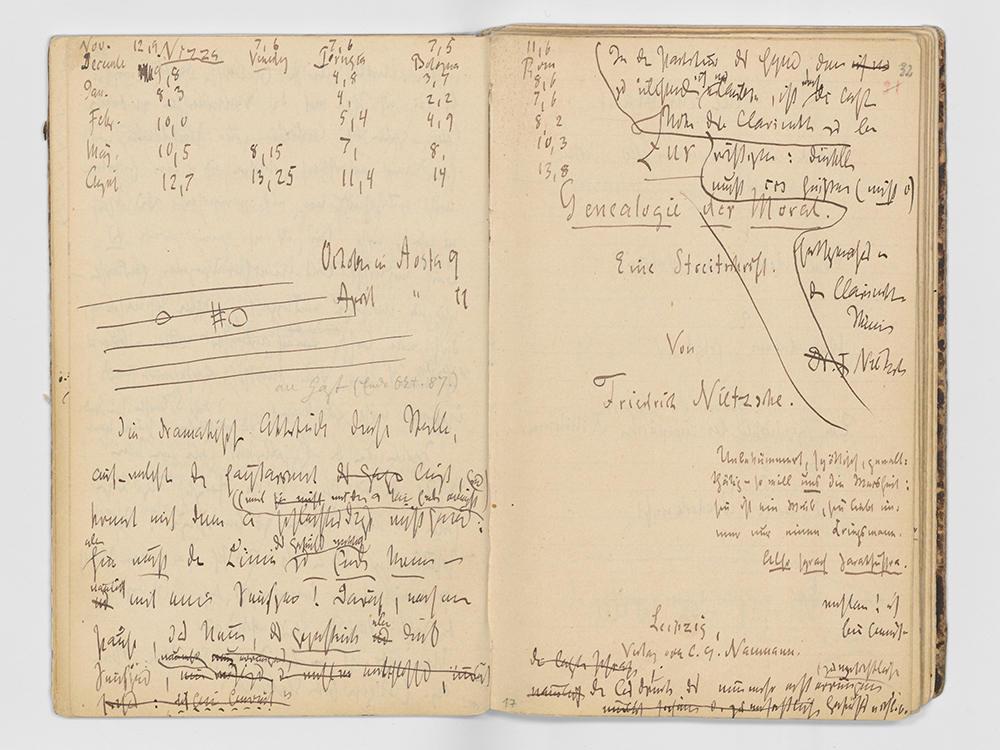

Since 2001, the German-Swiss publishing project Der späte Nietzsche (“The Late Nietzsche”) has been publishing his estate from 1885 to 1889 in full and true to the manuscripts for the first time. The project leader is Professor Hubert Thüring from the University of Basel. Together with the complete facsimile of the manuscripts, the estate is being documented and transcribed as it is found in his notebooks and workbooks, as well as on loose sheets in the Goethe and Schiller Archive in Weimar.

From 2021 to 2024, the team developed a digital edition of the typescript of On the Genealogy of Morality as part of the SNSF project Im Schreib-Druck, scheduled to go online at the end of 2025.

Hubert Thüring is an adjunct professor and university lecturer for modern German literature at the University of Basel. As part of various publishing projects, he has dealt intensively with Friedrich Nietzsche, his work and his reception for several years.

Basel celebrates: Friedrich Nietzsche's literary estate has been added to the UNESCO Memory of the World register

Friedrich Nietzsche’s literary estate has been part of the UNESCO Memory of the World register since April 2025. Part of this estate is housed in the University Library Basel and the State Archives of the Canton of Basel-Stadt, as well as in the Nietzsche House Foundation in Sils Maria. On 25 August 2025, all the relevant institutions in Weimar, where the majority of the estate is located, will receive a certificate.

On August 27, the event Basel feiert: Friedrich Nietzsches literarischer Nachlass gehört zum UNESCO-Weltdokumentenerbe will take place. Basel-based Nietzsche expert Dr. David Marc Hoffmann will use selected documents to demonstrate the explosive nature of the thinking, tradition and reception of the philosopher, who was appointed Professor of Greek Language and Literature by the University of Basel in 1869 at the age of 24. The opening address will be given by the Basel State Councilor and Director of Education Mustafa Atici.