Tracking down Metastases

When cancer cells detach from tumors and enter the bloodstream, they can develop into metastases. Scientists of the Department of Biomedicine at the University of Basel are investigating how this process exactly works – which allows them to develop new ideas for cancer therapy.

In recent decades, oncological medicine has made great progress. If a tumor is detected early, many types of cancer are now readily curable. But the chances of survival drop rapidly as soon as the tumor starts spreading: the development of metastases is responsible for around 90% of all cancer deaths, and patients with a metastatic disease are considered incurable. That is why scientists are increasingly focusing on combating metastases. In principle, it seems clear how metastases develop: cancer cells detach from the primary tumor and travel via the blood or lymphatic fluid to other tissues. Such as bone, lung or liver tissue, where they grow into metastases. However, the exact processes involved are still largely unknown. The Cancer Metastasis research group at the Department of Biomedicine has therefore set itself the goal of finding out more about the tumor cells that circulate in the blood as precursors to metastases. «If we can find a way to prevent the formation of these cells or destroy them, we can stop the progression of the disease and prolong patients' lives», says oncologist Prof. Dr. Nicola Aceto, head of the Cancer Metastasis Lab.

Cancer cells on the move

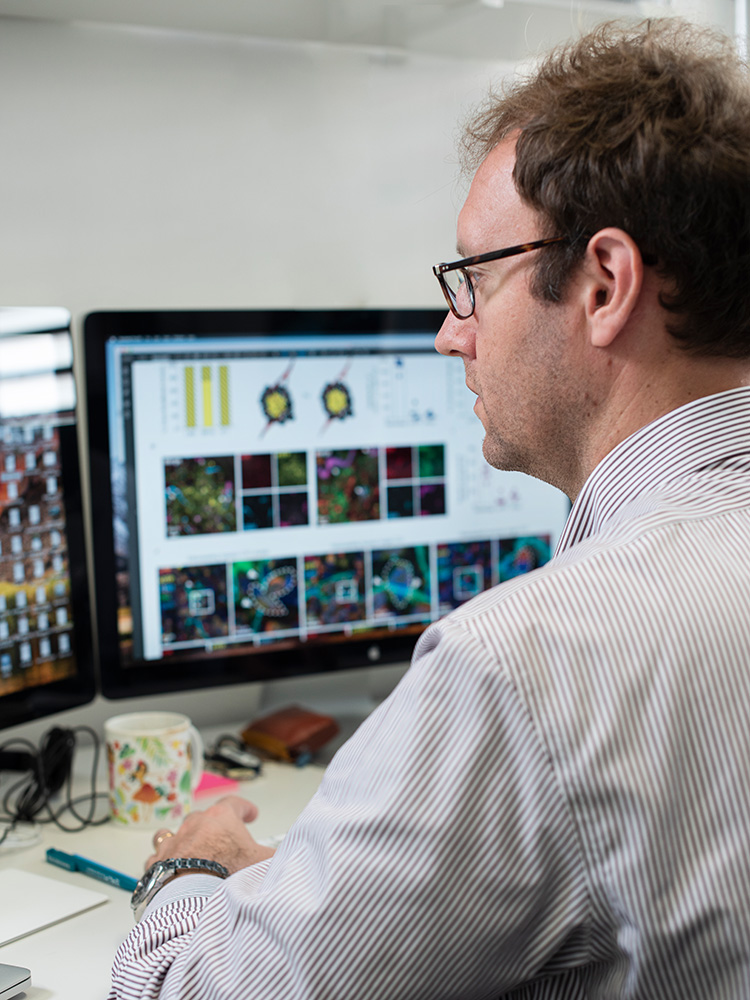

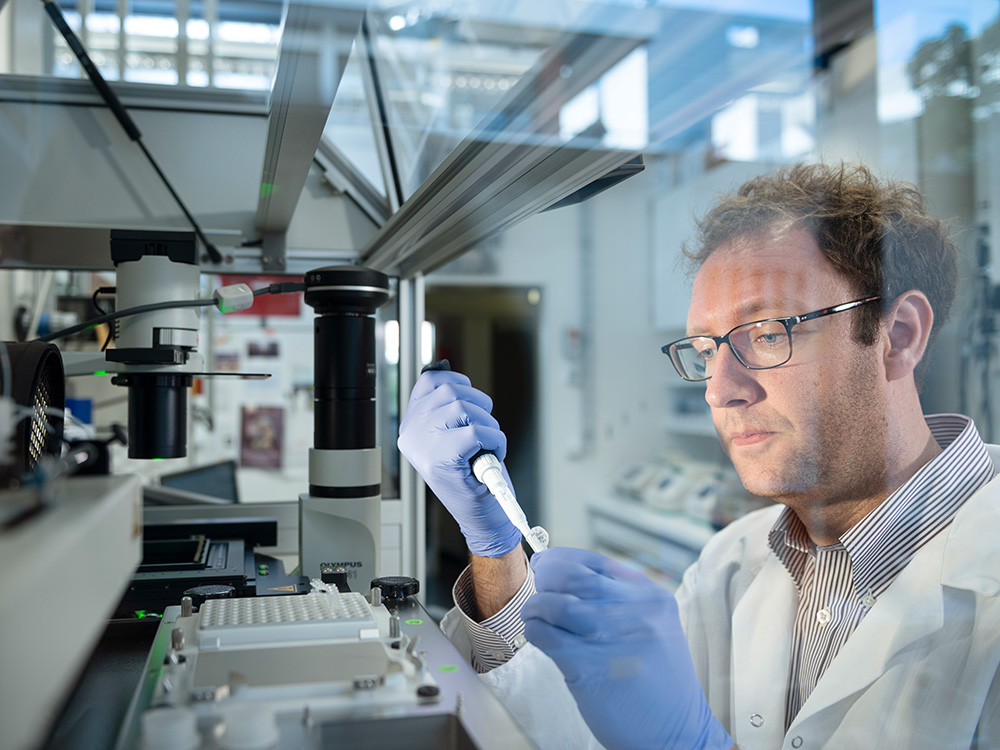

To characterize these so-called circulating tumor cells, they are filtered out of the blood of cancer patients, an endeavor not that easy: «A test tube of blood contains about 50 billion blood cells and only one to ten circulating tumor cells», says Aceto. However, tumor cells are a few thousandths of a millimeter larger than blood cells. To capture tumor cells the researchers are exploiting this difference in size by guiding the blood sample on a microchip through a labyrinth of increasingly narrower channels. While the blood cells flow through them unhindered, the somewhat thicker tumor cells get trapped.

Subsequently, the isolated circulating tumor cells can be studied in more detail using molecular biological methods. Aceto has also succeeded in keeping these cells alive and proliferating them in a petri dish, which is only possible with specifically coated surfaces, a special tissue culture medium and low oxygen levels. Such cell cultures can then be used to test drugs that may allow future therapeutic applications in the clinic.

Cell clusters are dangerous

Another important finding was that circulating tumor cells do not always travel individually, they may form clusters of two to 50 cells. These clusters play a key role in the development of metastases: In mice, clusters of circulating tumor cells led to metastases 20 to 50 times more efficiently than single cells. And with breast cancer patients, such clusters in the blood correlate with shorter life expectancy. One possible explanation, according to Aceto, is that such clusters of cells - more often than single cells - get stuck in the tiny capillaries and blood vessels of organs from where they can migrate into the surrounding tissue.

Aceto has therefore begun searching for substances that break down the cellular association of these clusters, thereby reducing the potential for metastases to form. He has already found at least one promising candidate: Screening a collection of existing drugs that are already approved for clinical use for their capacity to dissolve cell clusters identified a compound which is currently used to treat cardiac arrhythmias. At least in the mouse model, it also led to a reduction in metastasis formation. Now Aceto is testing this compound in breast cancer patients in collaboration with medical oncologists at the Basel University Hospital. «In this pilot study, however, the aim is to just show that the concept works in principle», Aceto says. The road to clinical trials and a future therapy is still long, he adds.

Meanwhile, his research group is already addressing another unsolved question in the development of metastases. Namely, why the cells detach from the primary tumor in the first place: «A tumor consists of billions of cells, and most of them stay where they are. Only a very few leave the tumor.» Again, Aceto sees promising starting points for future therapies; preventing cells from leaving the tumor also prevents metastases from forming.

Nicola Aceto has been appointed Associate Professor of Molecular Oncology at the Department of Biology at ETH Zurich and has left the University of Basel at the end of 2020.

Combating metastases at an early stage

Nicola Aceto's project «Holding hands: cell-cell junctions in breast cancer metastasis and resistance to therapy» investigates the function of cell-cell junctions in breast cancer. The project aims to elucidate the role of specific components of such junctions in the development of metastases and to investigate their involvement in signaling processes in order to develop tailored therapies. The ERC Starting Grant will be funded with a total of 1.75 million Euros over five years.