In Focus: Between Basel and Zimbabwe, Chipo Mellisa Kaliofasi is researching how Shona women have to fight for their property

Chipo Mellisa Kaliofasi came to Basel, thanks to a scholarship, and is working in the Department of History to obtain her doctorate. She is a member of the Shona people in Zimbabwe and researches inheritance laws and practices for Shona-speaking women during colonial times. To do so, she travels to the most rural districts of her home country.

31 July 2025 | Shania Imboden

Chipo Mellisa Kaliofasi is in the middle of her final preparations. In a few days, the 30-year-old will travel to Zimbabwe to conduct research for her doctoral thesis in history. Before her trip, she is meeting up with colleagues from the department for dinner. “We’re all friends,” she emphasizes. “Even before I came to Switzerland, the people here were incredibly supportive with my preparations.”

Kaliofasi grew up in Zimbabwe as a member of the Shona people (see box) and completed her master’s degree there. After the COVID-19 pandemic, she was ready for a change of place – to go out into the world, to Europe. She had already been preparing everything to do her doctoral thesis at a German university. But then came the acceptance from Basel – and everything changed.

Between Basel and Zimbabwe

The researcher feels very much at home in Basel: “I was already very drawn to the city because of its academic reputation, and I have never regretted the decision to do my doctorate here,” says Kaliofasi. Even if it means that she is separated from her family.

The doctoral student is a mother of three. Her children and husband live in Zimbabwe and support her from there. The distance is a challenge, but she visits her family as soon as she is in her home country for field research. “I’m happy to be able to see my family again soon,” she says briefly, preferring to talk about her work again.

A balancing act between laws and traditions

While still working as a research assistant in Zimbabwe, Kaliofasi became increasingly aware that the seemingly well-documented economic and political crises in the country represented only part of the reality. What lies beneath are deep-seated social fractures and cultural tensions. “What mainly drives me in my research is the desire to understand and combat the metaphysical, spiritual and structural inequalities and the resulting social conflicts.”

Her research focuses on the interplay between pre-colonial inheritance practices and the colonial legal systems that were introduced with British colonial rule. In her dissertation, Kaliofasi focuses on the role of Shona women and widows in dealing with property, belongings and inheritance law issues. Specifically, she investigates how Shona women in colonial Zimbabwe tried to secure their rights and property from 1896 to 1980.

Many of the legal structures and ways of thinking from the colonial era still have an impact today. At the same time, traditional inheritance practices persist in which spirituality, family interaction, and rituals play a vital role. Respect for the will of the deceased is particularly important to Shona culture. “We do not believe that death is the end. The deceased can still communicate with their loved ones, family members, and friends and make their wishes known to them. And we need to respect that.” According to Kaliofasi, an angry spirit brings misfortune to those who disregard its will.

The inheritance practice used varies depending on the family’s situation. “It is a balancing act that people then and now had to and have to manage,” says the researcher.

Archives, memory, and patriarchy

The role of women in Zimbabwean inheritance law is strongly influenced by patriarchy on several levels. Shona women – as well as other Shona people – were affected not only by colonial powers, but also by patriarchy both within their own culture and in colonial forms. “They had to try to navigate these two patriarchal contexts,” says Kaliofasi.

This summer, Kaliofasi will once again scour archives in Zimbabwe and interview people about their experiences. Since most of the archives in Zimbabwe have not yet been digitized, she has to search all the texts by hand, which takes a lot of time.

When it comes to the country’s social structures and spiritual customs, the academic mainly have to rely on the oral traditions of the Shona women. To do this, she travels far and wide within the country and visits many villages in order to gather first-hand experiences from older women and chiefs, capturing them with a recording device.

Kaliofasi not only learns about family misfortunes, but also about vengeful spirits and other spiritual interpretations. She is always touched by what the women report: “I hear a lot of emotional stories. Many women lost all their property after the death of their husbands as a result of laws, whether in the context of colonization or Shona traditions.”

Despite the often upsetting subject matter, she values the direct interaction with the people of Zimbabwe. “People like to tell their stories,” she says with a smile. But trusting oral sources also comes with methodological challenges: the narratives are subjective, of course, and there are occasional discrepancies, especially when it comes to dates. Nevertheless, the large number of similar reports produce a fairly objective overall picture.

Research with a mindset

For Chipo Mellisa Kaliofasi, however, it is important to present more than just facts. She wants her work to show the social and spiritual dynamics in her home country and incorporate into historical research how cultural systems shape people’s everyday lives. Her entire research project is marked by her interest in how these structures can be critically examined and changed through meaningful dialogue.

The Shona

The Shona are an African people with their own language, making up about 70% of the population of Zimbabwe. Their culture is rich in traditions; the Mbende Jerusarema dance, for example, is a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Traditionally, the right of inheritance of the Shona is based on belonging to the bloodline, with property inherited within it. While women marry into a bloodline, they are considered guests for their entire lives. If their husband dies, they have no inheritance rights. In the event of inheritance disputes, traditional chiefs and n’anga (traditional healers) are often called in to communicate with the deceased, share their wishes with living relatives and friends and thereby mediate.

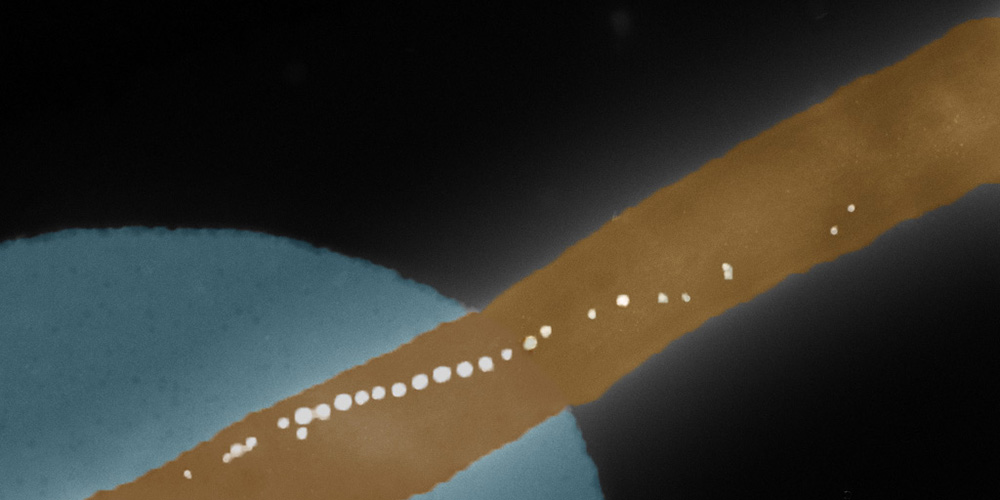

The Shona are a very spiritual people and maintain connections to their ancestors. N’anga are spiritual experts and key figures in spiritual communication between the dead and the living. They are consulted with respect to problems such as diseases or misfortune, since the Shona believe that these are the revenge of an angry spirit. A common n’anga method of divination is “bone-throwing,” which involves interpreting the spontaneous arrangement of symbolic objects to receive messages from ancestors or other spirits.

In Focus: the University of Basel summer series

The In Focus series showcases young researchers who play an important role in advancing the university’s international reputation. Over the course of several weeks, we will profile academics from various fields – a small representative sample of the more than 3,000 doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers at the University of Basel.