What the eyes reveal about the heart.

Text: Adrian Ritter

By examining the blood vessels of the eye, we can assess the health of vessels throughout the body. This method was developed in large part by researchers at the University of Basel. Now, it’s making its way into clinical applications.

In 1850, German physician Hermann von Helmholtz looked into the eye of a patient using his homemade ophthalmoscope — a revolutionary innovation. For the first time, it was possible to observe the back of the eye, particularly the retina and its blood vessels. Since then, generations of ophthalmologists have used the ophthalmoscope to examine the eye and diagnose eye-related diseases.

Today, we are at the brink of a new era in which eye exams could become a standard method of diagnosing other disorders, too. Henner Hanssen examines the eye using modern imaging methods, but none of his patients suffer from eye-related conditions. Instead, Hanssen, who is Head of Preventive Sports Medicine and Systems Physiology in the Department of Sport, Exercise and Health at Basel University, examines the fine blood vessels of the retina for signs of cardiovascular risk and disease.

Retinal vessels reveal insights to systemic health.

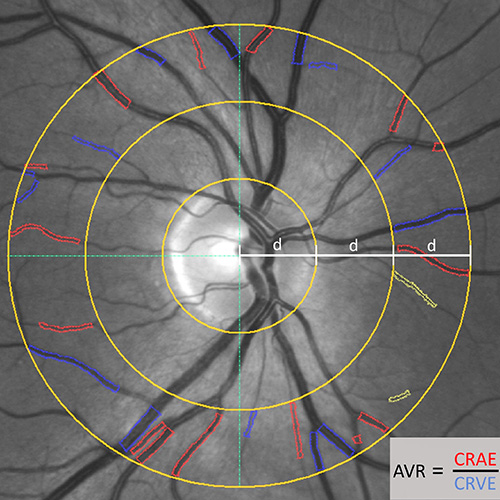

Hanssen is one of the world’s pioneers in a field known as retinal vessel analysis. Retinal vessel analysis relies on the fact that the retina is the only place in the body where tiny, otherwise inaccessible blood vessels can be examined without resorting to invasive methods. And research shows that these blood vessels reveal much about the circulatory health of the rest of the body. “They’ve turned out to be a true window into the heart, the brain and in fact the whole body,” says Hanssen.

The retinal blood vessels have a similar structure to those of the brain and the coronary arteries. So, the retina can be used to diagnose coronary heart disease, such as narrowed coronary arteries. In addition, changes to the fine vessels of the retina serve as early markers of diabetes or high blood pressure, which are cardiovascular risk factors, as well as heart attack or stroke, which are manifest cardiovascular diseases.

Detecting risk factors in children.

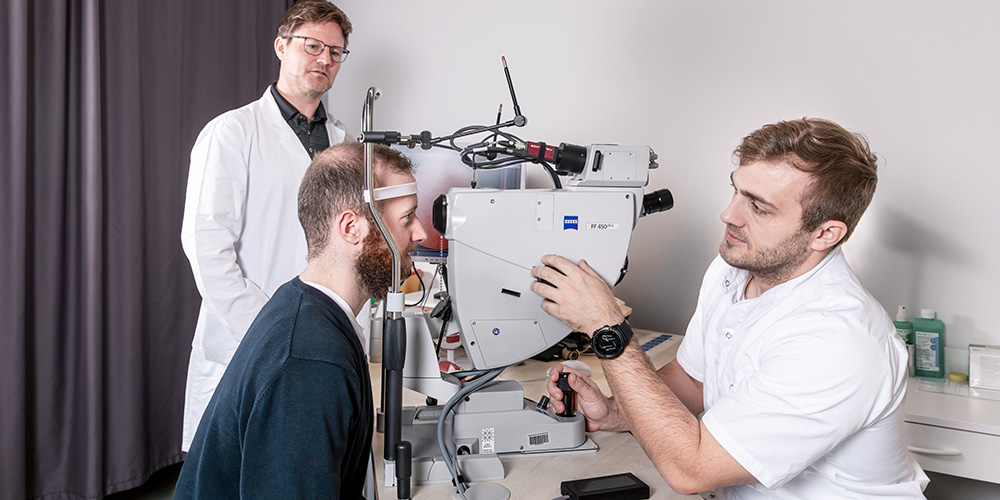

Unlike in the 19th century, these eye exams are no longer conducted using ophthalmoscopes. Now, physicians use a high-tech device that combines multiple imaging procedures. The exam takes around 20 minutes to complete and involves taking photos of the retina in order to, for example, measure the diameter of the blood vessels. The device also uses light stimulation to test vessel reactivity.

This process not only works on adults; it’s also effective in children. As Christoph Hauser, Head of the Vascular Laboratory in Hanssen’s group, explains: “We’ve examined around 1,500 children over the past few years. We identified minuscule changes in blood vessels to demonstrate how well the retina can be used to detect the risk of a child developing high blood pressure within the next four years.”

Should the eye exam reveal the presence or risk of cardiovascular disease, the next question is how to go about treating it. As a sports medicine physician, Hanssen focuses on exercise and sports. His research group demonstrated that exercise as therapy not only lowered blood pressure but also healed previously damaged blood vessels in the retina and small vessels throughout the rest of the body.

Early detection through eye exams.

Following a successful research phase, the exam procedure is now set to become a standard testing method in clinical settings. “We’re working to get retinal vessel analysis implemented in the guidelines of international medical societies,” says Hanssen. Patients who stand to benefit the most from this procedure are those with a low to moderate risk of cardiovascular disease. This includes people who are overweight and those with high blood pressure or chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, which also damage blood vessels.

“Regular examinations of patients’ retinas could tell us about the health of their blood vessels and the extent to which lifestyle changes or medications can improve it,” says Hanssen. His research group demonstrated that when retinal vessel analysis is added to the standard diagnostic procedures, such as electrocardiography and blood tests, 20 percent of patients receive more precise risk assessments for cardiovascular disease. “As a supplementary diagnostic tool, retinal vessel analysis stands to improve prevention and therapy significantly,” says Hanssen.

The novel diagnostic tool may also prove useful in school medical exams. “But that will require a cost-benefit analysis,” says Hauser. While children rarely have cardiovascular diseases, they certainly display risk factors, such as high blood pressure or a genetic propensity for high cholesterol. Before this new diagnostic tool can be implemented more broadly, it will need to become simpler and more cost-effective, emphasizes Hauser, saying: “Artificial intelligence will certainly help us reach these goals and at least partially automate the analysis process.”

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (May 2025).