From maws to mouths.

Text: Angelika Jacobs and Noëmi Kern

Whether fishes or great apes, vertebrates have developed an incredible variety of mouth types. What do we know about their history and origins?

Where does the mouth originate from?

It could barely look more different from the brain, and yet many structures of the vertebrate mouth — such as the jaw, teeth or palate — develop from neuronal precursor cells. In humans, these “neural crest cells” emerge during the third week of pregnancy, when the central nervous system forms as a tube-like structure on the back of the embryo. From the fourth week onward, these cells detach and migrate to the front of the head, where they develop into cartilage, bone and teeth. These cells were discovered by the Basel-based Professor of Anatomy and Physiology Wilhelm His (1831-1904) and are still the subject of research at the University of Basel today. Specifically, Patrick Tschopp’s team is investigating how different embryonic precursor cells — including neural crest cells — can produce the same tissue type: namely, the bones of the face, the limbs and the torso.

Predators and prey.

All organisms need to ingest and utilize nutrients. Early vertebrates filtered their food from the water or lived parasitically — like the present-day lamprey. Then, around 430 million years ago, came one of the giant leaps in evolution: the innovation of a mouth with a jaw. This provided access to completely new sources of food, as it could be used to grab and chew both plants and animals. Animals became both predators and prey.

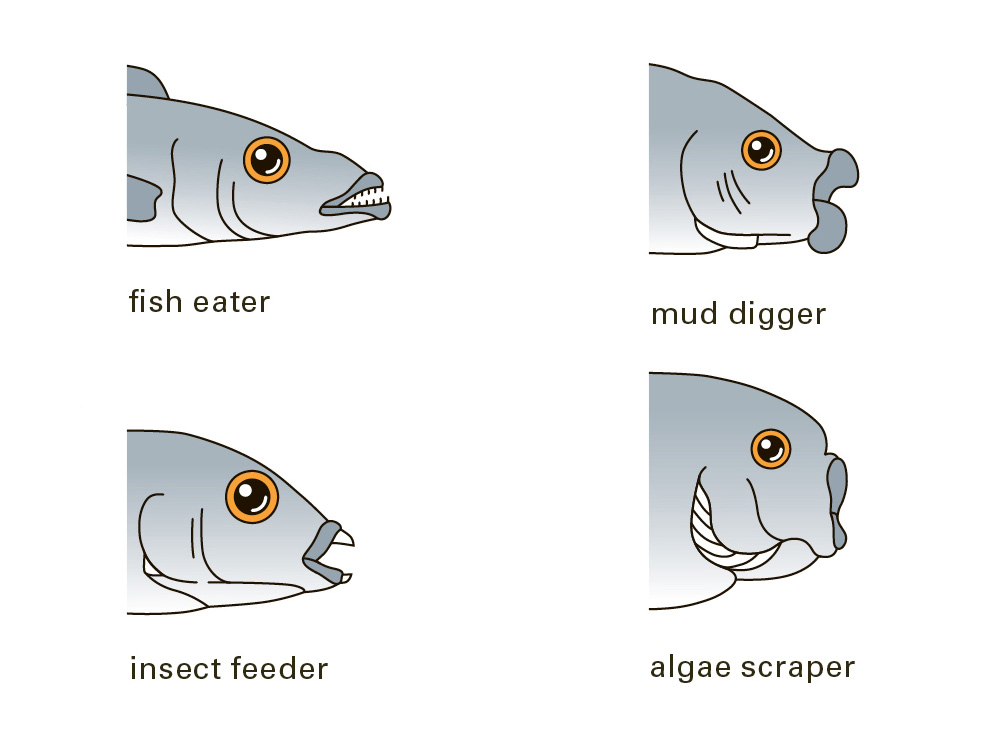

With their diverse shapes of jaws, vertebrates specialized in wide-ranging food sources and found their individual niches. One prominent example of how evolution exploits all potential food sources are Darwin’s finches — named after their discoverer — on the Galapagos Islands, with their different shapes of beaks. Likewise, the cichlid fishes in Lake Tanganyika have developed specialized jaws, and the research group led by Walter Salzburger is using the breathtaking diversity of these fishes as an example to investigate fundamental mechanisms of evolution.

Microtraces on teeth.

What did an animal eat? Was it ridden? Did it chew on the bars of its cage due to stress? Dorota Wojtczak, a researcher in integrative prehistory and archeological science, analyzes animal teeth for signs of wear and clues from food residues. The tiny cavities and striations on the surface of the teeth reveal much about an animal’s life: Soft foods such as straw and hay leave different marks than seeds. Bridles have a distinctive way of wearing down the teeth of animals that have been ridden. Sometimes, human interference can be detected: When the skeleton of a young brown bear was discovered in Augusta Raurica, its teeth were found to have been filed down to make it less dangerous.

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (May 2025).