Each person is their own clock

Text: Oliver Klaffke

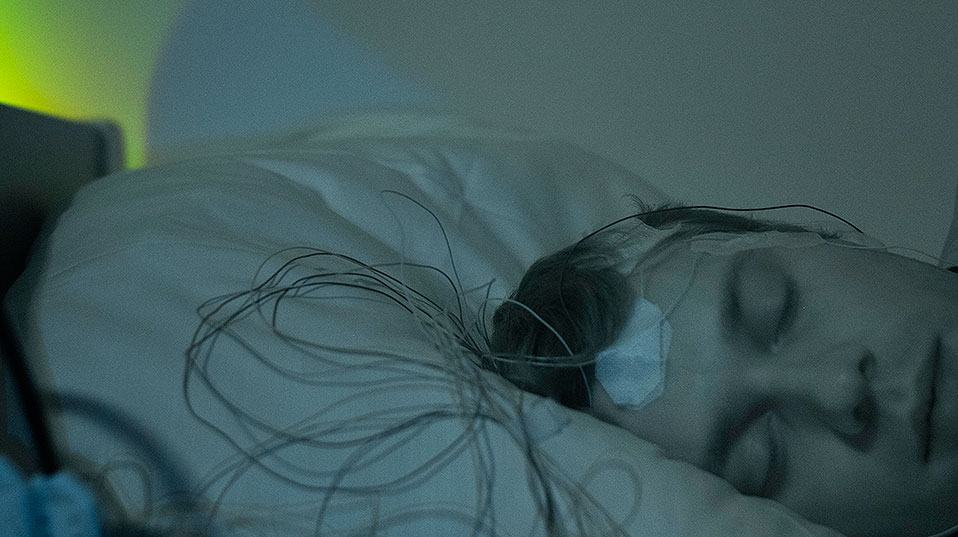

Human beings have their own sleep-wake cycles, and these rhythms can be disturbed by light emitted from smartphones and tablets. At the Psychiatric Hospital of the University of Basel (UPK), Christian Cajochen’s team is examining these rhythms in human beings.

It is only when one no longer knows whether it is day or night, whether it is time to get up or time to go to bed, or time to eat, that one is really cut off from one’s environment. “Those are exactly the conditions we create in our laboratory in order to be able to examine sleep rhythms in humans,” says Professor Christian Cajochen of the UPK Basel. His work group is studying individuals’ inner clocks, clocks, which function even without any external natural Zeitgeber (such as the day-night cycle) or social Zeitgeber (such as meal times or television broadcast times).

The subterranean sleep laboratory has thick walls through which no sound from outside can penetrate, neither the noise from the motorway nor from Basel’s airport – and certainly not the sound of birdsong in the morning. In this remoteness, each test subject’s rhythm has its own individual beat. “Each person has their own rhythm, with phases of waking and of sleeping. In one individual, these may be a little longer and in another a little shorter than 24 hours,” explains Cajochen. “Normally, this rhythm is adjusted to the environment by means of external Zeitgeber.”

Mood and time of day

Cajochen’s area of expertise is chronobiology, a science which in recent years has done away with the idea that human beings are organisms without any time of their own – permanently resilient, always ready for action, and ever able to perform to the very limit. This idea underpins the self-conception of our modern achievementoriented society. “Our results throw a whole different light upon people’s relationship with time,” explains Cajochen. As with probably most animals, human beings are creatures who are subject to an internal temporal rhythm, a rhythm which cannot simply be changed at will. Physiological processes, such as digestion and the metabolism of medicinal drugs, differ depending on the time of day. A person’s mood is also dependent on the time of day, as is their ability to perform complex tasks: “Human beings are clocks, and each person is their own clock.”

In the sleep laboratory in Basel, Cajochen and his colleagues have studied the connection between well-being and the time of day. For all test subjects, the levels on their “Happiness Index” were lowest in the morning, between 3 am and 6 am. They were happy, or even very happy, from the early afternoon at around 2 pm through to around 8 pm in the evening. A similar pattern was recently discovered by chronobiologists in the USA when they analyzed around half a billion Twitter tweets: negative tweets were sent mostly between midnight and around 7 am with a definite low point in the mood of the tweeters at around 3 am. These results are only small pieces in the mosaic of our understanding of the extent to which people are at the mercy of their own internal clocks.

Unnatural light spectrum

“Take the example of the production of melatonin,” says Cajochen. This hormone ensures that an individual becomes tired and falls asleep and eventually wakes up again. Since less melatonin is produced in our later years than in our early years, older people tend to develop age-related early awakenings and young people tend to sleep till all hours. “We were able to show that the production of melatonin is influenced by the color spectrum produced by the screens of computers, smartphones, and tablets,” says Cajochen. Compared to light from electric bulbs or neon tubes, the color spectrum of these screens, which work using LEDs, has a very high proportion of blue light: “And this, apparently, slows down the production of melatonin in the body.” Cajochen and his colleagues measured the concentration of melatonin in the saliva of test subjects who had been exposed to the LED light from screens and of subjects who had been exposed to light from non-LED screens. Those who had spent their time exposed to light with a high proportion of blue light had, shortly after midnight, melatonin levels which were approximately 15 percent lower than in the other group. The researchers suspect that this is the reason this group also became tired later than the others.

The work of Cajochen and other chronobiologists helps in understanding societal changes, since we now live in a “multiscreen online society,” as Cajochen puts it. Young people spend around 53 hours per week in front of screens and so are exposed to a light spectrum that is not found naturally or in any previous form of artificial lighting system. That could change the wake-sleep cycle and lead us to become a society in which people are constantly overtired. In the meantime, there are already cell-phone apps that adapt the spectrum of the screen lighting to the time of day.

“Blue light is like an espresso”

Cajochen was, however, also able to determine an interesting effect of blue light on mental performance. In this experiment, test subjects had to learn new words in the evening and then later identify them correctly. Individuals who had learned the words in light emitted by LED monitors had a success rate of 60 percent. Those who had learned in light emitted by a non-LED monitor had a success rate of barely 50 percent. This result might indicate that a lower level of melatonin in the evening has a positive influence on attention. “Blue light is like an espresso,” says Cajochen.

So does this mean that if you want to learn something, you should get a lamp which emits light with a high proportion of blue in it? That could work, but only in the short term. The slowed production of melatonin has a side effect that causes sleepiness in the long term: the high proportion of blue light and the resulting delay in becoming tired cause a shift in the day-night cycle of the test subjects and so disrupts their individual rhythm. Staying up later and nevertheless getting up as early as before eventually creates a sleep deficit that has to be compensated for. “People must satisfy their need to sleep,” explains Cajochen. At some point, even “sleep machos” – as Cajochen terms those who power on at the cost of their sleep – have to hit the hay.

16-hour performance capacity

Early in his scientific career, Cajochen addressed the question of how long an individual can keep going and perform well without sleep. “More than sixteen hours is not possible,” he says. He measured a number of physiological parameters which indicate fatigue and a heightened need for sleep. Alongside the plasma level of the melatonin, these include the circulation of blood in the fingers, the frequency of slow eye-movements, and the occurrence of episodes of microsleep.

No matter which one of these variables Cajochen’s team looked at, after a waking phase of approximately 16 hours the fatigue parameters rose. “That is a clear indication that after a certain period of waking, performance falls rapidly.” Recognizing this was one of the greatest achievements of chronobiology. Studies in medical journals laid the myth of the high performance “sleep macho” to rest: After a night without sleep, surgeons make a fifth more mistakes and require around 15 percent longer for procedures. Medical residents who drive home after a 24-hour shift cause 165 percent more car accidents than colleagues whose shifts were shorter.

“These studies ensured that in the USA limits were set to doctors’ working hours,” says Cajochen. The principal beneficiaries of this were the patients, who were now treated by doctors who were more likely to be well-rested. This is a good thing, since studies have shown that the ability to concentrate and the reaction times of someone who has been awake for 24 hours are similar to those of a person with a blood-alcohol level of almost 0.1 percent. A person like that should not be in an operating room or in a position of responsibility, or be behind a steering wheel. They belong in bed.

Test: Lark or owl?

Are you more an evening or a morning person – an owl or a lark? The Centre for Chronobiology has developed an online questionnaire on sleeping and waking behaviors that can help you to discover your own so-called chronotype.