A founding myth: the Soviet Union’s Rütli

Till Hein

In September 1915, Lenin, Trotsky, and around three dozen other left-wing politicians and activists from twelve European countries met at Zimmerwald near Bern. They dreamed of uniting the workers’ movement internationally and stopping the First World War. A hundred years later, Eastern European historians in Basel are shedding light on this secret meeting – and its strange afterlife in the memory cultures of East and West.

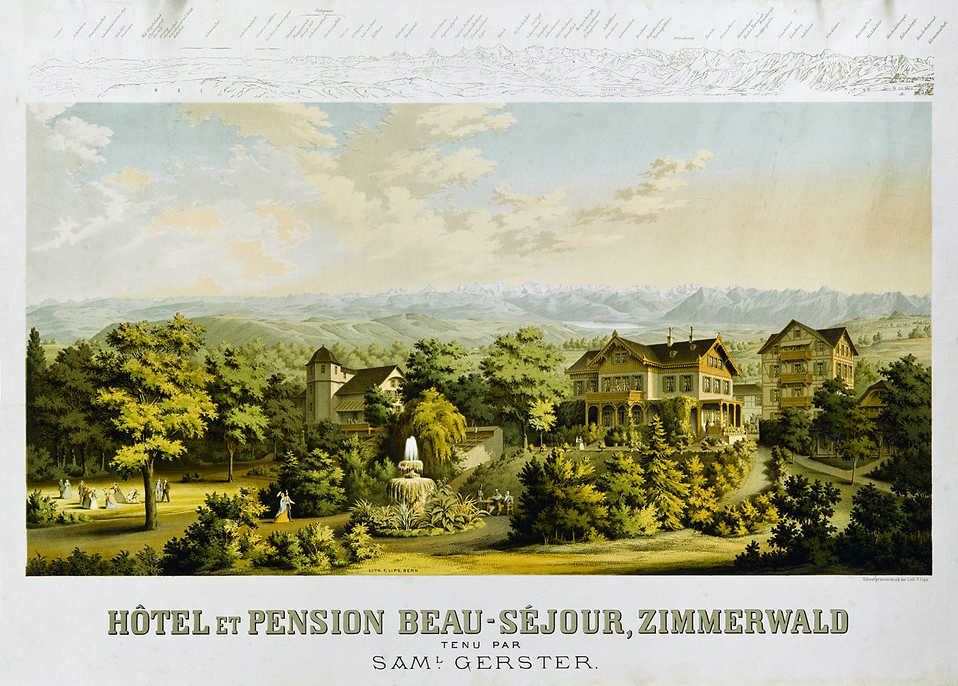

It is September 5, 1915. The rolling hills of the Längenberg are bathed in warm light by the midday sun. Robins and skylarks are twittering. Horsedrawn carriages are wending their way through the pasturelands to the south of Bern, heralding the arrival of around three dozen foreigners. The men claim to be bird lovers who want to hold an ornithology conference in the “Beau Séjour” guesthouse in Zimmerwald.

The village is still barely geared up for tourists. There are only a few guest beds available, so some of the supposed bird fanciers are put up privately with the vet or the postman. In reality, the guests are prominent left-wing politicians and activists from twelve European countries, among them Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and Leon Trotsky. At the invitation of the Bernese Social Democrat Robert Grimm, they are meeting to hatch a plot. Their shared goal is to unite the workers’ movement internationally and end the slaughter in the trenches of the First World War.

For four days, they will argue, debate, and concoct plans in Zimmerwald. Many of those taking part are regarded in Switzerland as leftist radicals and enemies of democracy. However, although a country policeman turns up at the “Beau Séjour” and fines the landlord for disturbance of the peace – the dancing, partying, and singing had carried on too late into the night – the activists are not recognized and the secret meeting is not broken up.

Eventually, they will produce their “Zimmerwald Manifesto”, which includes the following call to arms: “Proletarians! Since the outbreak of war, you have devoted your energies to the service of the ruling classes. Now you need to stand up for your own cause, the sacred goals of socialism, the liberation […] of the enslaved classes, by engaging in relentless class war. […] Across borders, across the reeking battlefields, across the ruined towns and villages, we issue this summons: proletarians of all countries, unite!”

Two weeks later, long after the foreign guests had left, the organizer of the secret meeting, Robert Grimm, produced a report for the Berner Tagwacht newspaper and published the manifesto. The Swiss political class was outraged. They had let themselves be fooled. “That is probably why people around here went to such lengths to suppress the memory of this historical event,” says Frithjof Benjamin Schenk, Professor of Eastern European History and head of the history department at Basel University.

The manifesto says nothing about concrete action to stop the war. “It is the expression of a political compromise,” Schenk explains. A small faction around Lenin pursued more radical goals at the conference. For them, the language used in the manifesto was too general. They wanted to set out concrete ways of waging class war and, in the process, to spark a proletarian revolution – all over the world. In 1917, this radical strategy would prove successful in Russia, at least. “Lenin’s plan was not included in the Zimmerwald Manifesto,” Schenk says, “yet later the Bolsheviks transformed Zimmerwald into a mythical birthplace for their state” – a sort of Rütli for the Soviet Union.

A suppressed legacy

“Throughout the socialist world, every child learned about Zimmerwald at school,” Schenk explains. On many Soviet maps of the world, the village was the only Swiss place name shown. “In Switzerland, by contrast – especially in Zimmerwald itself – the legacy of 1915 was seen as very problematic for a long time.”

A hundred years after the conference, what interests Schenk and his colleagues is not just the event itself and its historical significance, but its strange afterlife in East and West. A few years ago, the history department at Basel University received a call from the council offices in Zimmerwald. The municipal secretary had come across a file of old papers and was unsure of what to do with it. He diligently made inquiries as to whether the documents might be of interest to scholars.

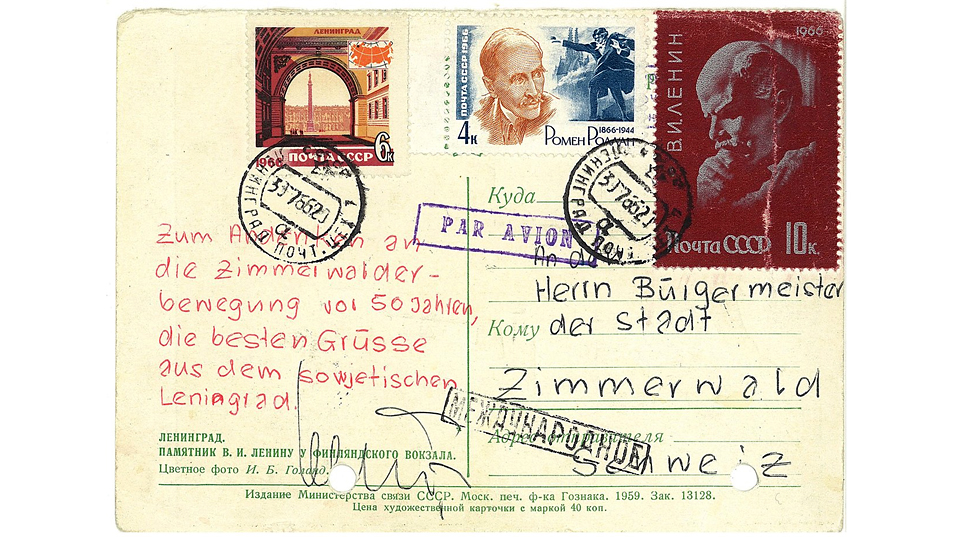

The Eastern European historian Julia Richers, now a professor in Bern, went through the material. In it she found a wealth of fascinating letters and postcards written to Zimmerwald by people from the Soviet Union – addressed to the “Director of the Lenin Museum,” for example. Yet, the last thing the people of Zimmerwald wanted was to set up such a museum. “After the general strike of 1918, in particular, the prevailing mood in Switzerland was firmly anti-communist,” Schenk says.

Most of the communications are about Lenin. Fans of Zimmerwald in what is now St Petersburg send greetings from the “Soviet to the Swiss Leningrad”. The workers’ collective at a salt mine in eastern Ukraine writes, “We would like to know how the memory of this great man lives on in your town.”

The council office sends back letters to set the record straight, making clear that people in Switzerland want nothing to do with “communist agitation”. And pointedly, “socialist greetings” are countered with “democratic greetings”. In 1945, when a history enthusiast from Lausanne asks for information about the Zimmerwald Conference, the municipal secretary goes through the roof. “I am not inclined to furnish a political extremist with material that could be of use to a subversive organization,” he barks at the man.

In the mid-1950s – after the death of Stalin – the cult of Lenin becomes increasingly important in the USSR. Because of Lenin’s involvement in the 1915 conference, Zimmerwald takes on “an almost mythical significance” in the Soviet Union, according to Schenk. And the municipality responds. In 1962, a ludicrous provision for the “protection of healthy living” is added to Zimmerwald’s building regulations, prohibiting the erection of any memorial stones or plaques. Reminders of the “communist conference” are to be banned for all time.

Three years later, on the 50th anniversary of the meeting, conservative forces organize the “Second Zimmerwald Conference” as an anti-communist commemoration. The next step comes in 1971, when the municipality has the building where Lenin stayed during the conference – long known locally as the “Lenin house” – torn down.

According to Schenk, “It was only in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, that the situation in Zimmerwald became less tense.” In 1996, festive parades are held in the village to mark its 700th anniversary. These feature not only celebrations of the Celtic past and present-day rural life, but a figure dressed up as a bald man with a striking goatee, in a parody of Lenin. The famous revolutionary is no longer a bogeyman but can now take his place – with a wink to the crowd – in the village’s history.

Benjamin Schenk is fascinated by such shifts and reassessments of historical events and characters. In early September 2015, he and Julia Richers organized an international conference to mark the 100th anniversary of the Zimmerwald Conference, which looked at communist and socialist sites of memory in Europe from a comparative perspective. One of its themes was the commercialization of memory, for example, in museums in Germany, which show a trivialized version of life in the GDR – and then sell souvenirs. Other speakers discussed the changing history of Lenin memorials in the Ukraine and Russia.

The conference ended with a trip to Zimmerwald, attended by scholars from 16 countries. There they were struck by another oddity. There is still no memorial in the village on the site where the “Lenin house” once stood. Instead, it is now home to a local bank.

Frithjof Benjamin Schenk is Professor of Eastern European History at the University of Basel.