Gene therapy to reverse vision loss in macular degeneration

Researchers have developed a strategy that has the potential to improve vision in patients with macular degeneration in the future. Using a gene therapy, they sensitized blind retinas of mice and human organ donors to near-infrared light. The team based at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel (IOB) has published its results in the journal Science.

05 June 2020

About 200 million people worldwide are affected by macular degeneration. The macula is a small light-sensitive structure at the back of the eye. If it degenerates, those affected retain their peripheral vision, but over time they lose the center of their field of vision. Treatment can delay progression, but it is not yet possible to restore the lost light sensitivity.

“Restoring photosensitivity can ultimately improve the quality of life of those affected and their ability to participate in everyday life,” says Professor Botond Roska, Professor of Vision Research at the University of Basel and Director of the IOB. To achieve this goal, the researchers sensitized the retinal cells of mice and organ donors to near-infrared light using gene therapy.

Inspired by nature

Although infrared light is invisible to the naked human eye, we can perceive it as heat. Longer infrared wavelengths can cook food, but near-infrared light is closer to the visible spectrum of the human eye and is cooler in comparison. Certain animals, however, do possess infrared vision: snakes for example use heat-sensitive proteins, known as Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) ion channels, to perceive the infrared radiation emitted by their prey.

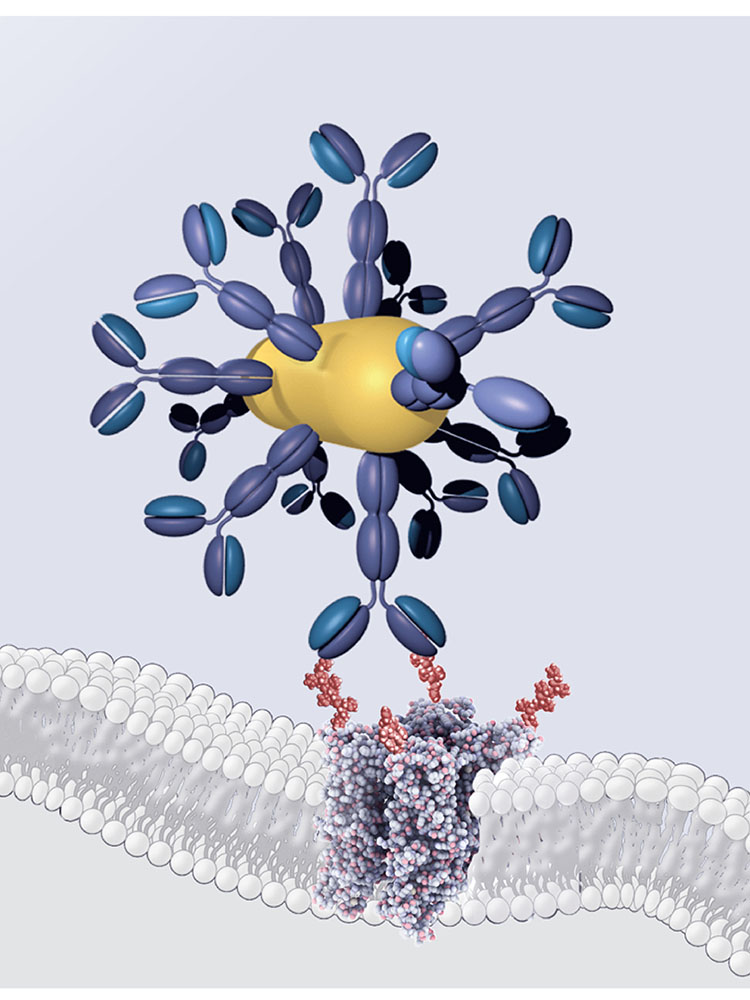

Inspired by this example from nature, the researchers developed a gene therapy to equip blind retinal cells with an infrared sensor. The system consists of three components: a DNA segment that codes for a TRP ion channel, a gold nanoparticle that absorbs near infrared light, and an antibody that tethers the nanoparticle to the ion channel. The researchers used a viral gene shuttle and microinjection to introduce the components into the retinal cells.

The gold nanoparticles absorb near-infrared light and then emit a small amount of heat. In response, the TRP ion channels open and trigger nerve impulses similar to those in normal vision.

Promising results in initial tests

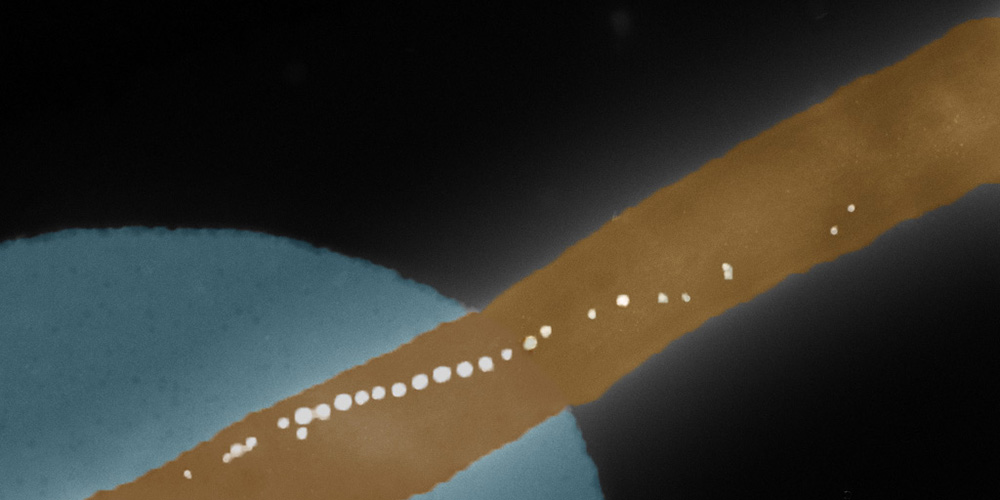

The researchers subsequently tested their gene therapy on two model systems: on mice that develop retinal degeneration and go blind due to a gene modification, and on retinas from human organ donors.

In the first case, the researchers investigated the behavior of the treated mice in a learning experiment in which the mice were trained to react to a light signal in the near-infrared range. This confirmed that the animals who received the gene therapy were able to perceive the near-infrared light. Measurements of nerve impulses also showed that the signals reach the brain areas for processing visual stimuli. Further tests with retinas from organ donors confirmed the functionality of the system.

Special approach needed for macular degeneration

The new study builds on the researchers’ ongoing efforts to treat complete blindness with a technique called “optogenetic therapy”. In this approach, light-sensitive proteins are introduced into the retinal cells by viral gene shuttles. This therapeutic concept is currently in clinical trials, but is unsuitable for macular degeneration.

The procedure is based on glasses that project bright visible light onto the retina. However, the light projection would be overwhelming to those patients who have only lost their central vision. A therapy against vision loss due to macular degeneration therefore requires light of a different wavelength, which functioning cells in the retina cannot see, explains Dr. Dasha Nelidova, a postdoc in Botond Roska’s laboratory and first author of the publication. The researchers hope that their approach will one day be used to re-sensitize the macula in patients who still retain their peripheral vision.

Original source

Dasha Nelidova, Rei K. Morikawa, Cameron S. Cowan, Zoltan Raics, David Goldblum, Hendrik Scholl, Tamas Szikra, Arnold Szabo, Daniel Hillier, Botond Roska

Restoring light sensitivity using tunable near-infrared sensors

Science (2020), doi: 10.1126/science.aaz5887

Further information

Sabine Rosta, communications officer IOB, phone +41 76 336 77 74, email: sabine.rosta@iob.ch