Droughts in the sixth century paved the way for Islam

Extreme dry conditions contributed to the decline of the ancient South Arabian kingdom of Himyar. Researchers from the University of Basel have reported these findings in the journal Science. Combined with political unrest and war, the droughts left behind a region in disarray, thereby creating the conditions on the Arabian peninsula that made possible the spread of the newly emerging religion of Islam.

16 June 2022

On the plateaus of Yemen, traces of the Himyarite Kingdom can still be found today: terraced fields and dams formed part of a particularly sophisticated irrigation system, transforming the semi-desert into fertile fields. Himyar was an established part of South Arabia for several centuries.

However, despite its former strength, during the sixth century CE the kingdom entered into a period of crisis, which culminated in its conquest by the neighboring kingdom of Aksum (now Ethiopia). A previously overlooked factor, namely extreme drought, may have been decisive in contributing to the upheavals in ancient Arabia from which Islam emerged during the seventh century. These findings were recently reported by researchers led by Professor Dominik Fleitmann in the journal Science.

Petrified water acts as climate record

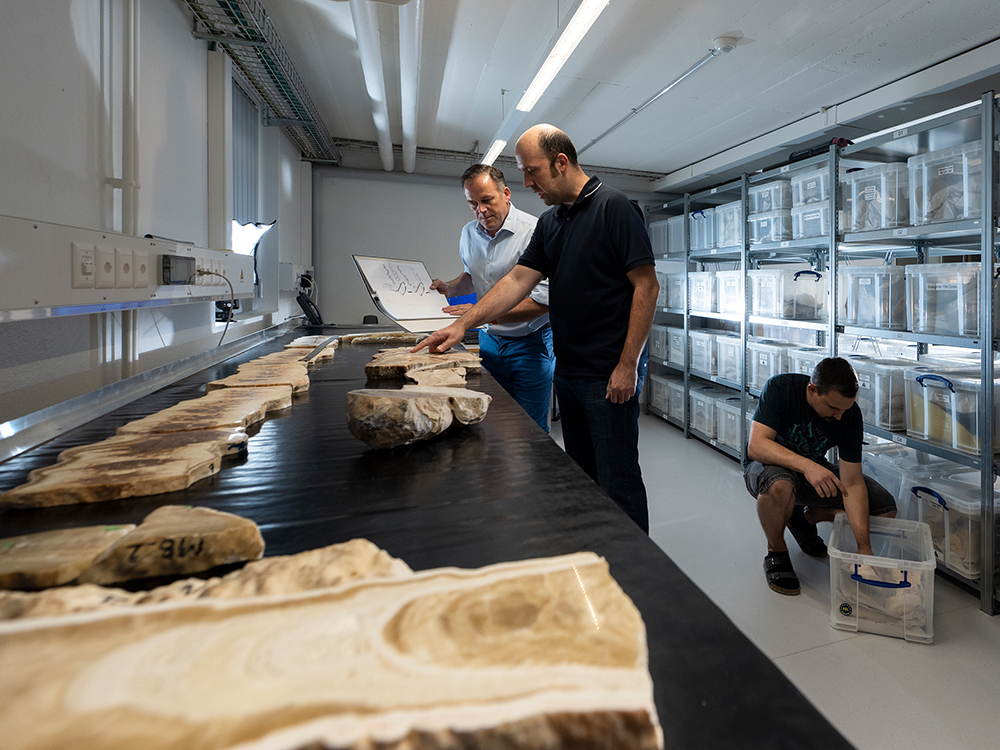

Fleitmann’s team analyzed the layers of a stalagmite from the Al Hoota Cave in present-day Oman. The stalagmite’s growth rate and the chemical composition of its layers (see box) are directly related to how much precipitation falls above the cave. As a result, the shape and isotopic composition of the deposited layers of a stalagmite represent a valuable record of historical climate.

“Even with the naked eye you can see from the stalagmite that there must have been a very dry period lasting several decades,” says Fleitmann. When less water drips onto the stalagmite, less of it runs down the sides. The stone grows with a smaller diameter than in years with a higher drip rate.

Isotopic analysis of the stalagmites layers allows researchers to draw conclusions about annual rainfall amounts. For example, they discovered not only that less rain fell over a longer period, but that there must have been an extreme drought. Based on the radioactive decay of uranium, the researchers were able to date this dry period to the early sixth century CE, albeit only with an accuracy of 30 years.

Detective work in the case of Himyar’s demise

“Whether there was a direct temporal correlation between this drought and the decline of the Himyarite Kingdom, or whether it actually didn’t begin until afterwards – that was not possible to determine conclusively from this data alone,” explains Fleitmann. He therefore analyzed further climate reconstructions from the region and combed through historical sources, collaborating with historians to narrow down the time of the extreme drought, which lasted several years.

“It was a bit like a murder case: we have a dead kingdom and are looking for the culprit. Step by step, the evidence brought us closer to the answer,” says the researcher. Helpful sources included, for example, data about the water level of the Dead Sea and historical documents describing a drought of several years in the region and dating to 520 CE, which do indeed connect the extreme drought with the crisis in the Himyarite Kingdom.

“Water is absolutely the most important resource. It is clear that a decrease in rainfall and especially several years of extreme drought could destabilize a vulnerable semi-desert kingdom,” says Fleitmann. Furthermore, the irrigation systems required constant maintenance and repairs, which could only be achieved with tens of thousands of well-organized workers. The population of Himyar, stricken by water scarcity, was presumably no longer able to ensure this laborious maintenance, aggravating the situation further.

Political unrest in its own territory and a war between its northern neighbors, the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, spilling over into Himyar, further weakened the kingdom. When its western neighbor of Aksum finally invaded Himyar and conquered the realm, the formerly powerful state definitively lost significance.

Turning points in history

“When we think of extreme weather events, we often think only of a short period afterwards, limited to a few years,” Fleitmann says. The fact that changes in the climate can lead to states being destabilized, thereby changing the course of history, is often disregarded. “The population was experiencing great hardship as a result of starvation and war. This meant Islam met with fertile ground: people were searching for new hope, something that could bring people together again as a society. The new religion offered this.”

That does not mean to say the drought directly brought about the emergence of Islam, emphasizes the researcher. “However, it was an important factor in the context of the upheavals in the Arabian world of the sixth century.”

Original publication

Dominik Fleitmann et al.

Droughts and societal change: the environmental context for the emergence of Islam in late Antique Arabia

Science (2022), doi: 10.1126/science.abg4044

Further information

Professor Dominik Fleitmann, University of Basel, Department of Environmental Sciences, phone: +41 61 207 61 12 / +41 76 473 59 89, email: dominik.fleitmann@unibas.ch

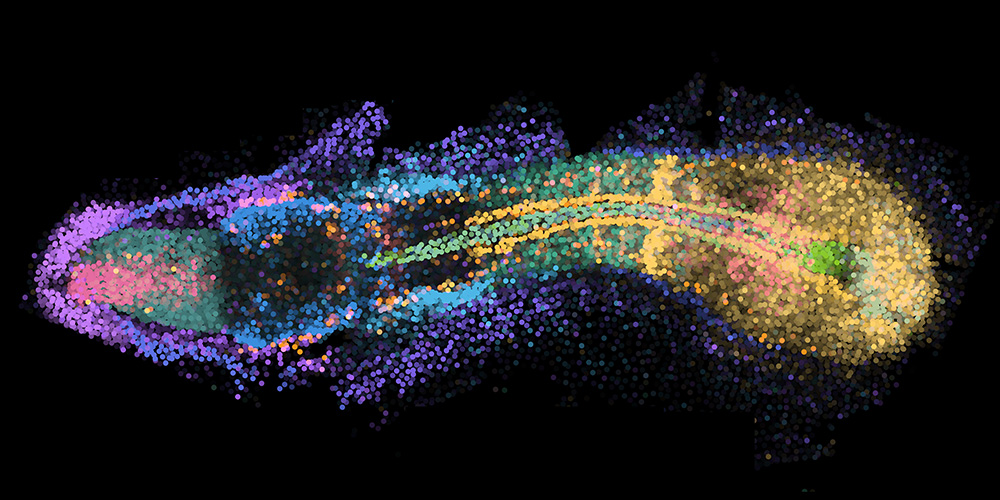

Precipitation and Isotopes

In tropical and sub-tropical regions, there is a connection (correlation) between the amount of precipitation and its isotopic composition, also known as the “amount effect”. The more it rains, the more the ratio between the lighter and heavier oxygen isotopes, 16O and 18O, shifts in favor of the lighter 16O in the precipitation. These changes are recorded in the stalagmite from Oman, as it is formed from dripping rainwater. Based on isotopic measurements of the stalagmite’s limestone layers, it is possible to determine the exact ratio of 16O and 18O and, in combination with uranium dating, to reconstruct how much it rained at what point in time.