In Focus: Alaa Dia draws maps of asylum centers that show more than mere architecture

The academic and professional world often encourages crossing borders, both literal and metaphorical. Such is the tale of Alaa Dia: Born and raised in Lebanon, Dia took his academic pursuits to Switzerland. Over the years, his work transitioned from an architectural perspective to a theoretical understanding of space, cartography, and borders.

03 August 2023 | Catherine Weyer

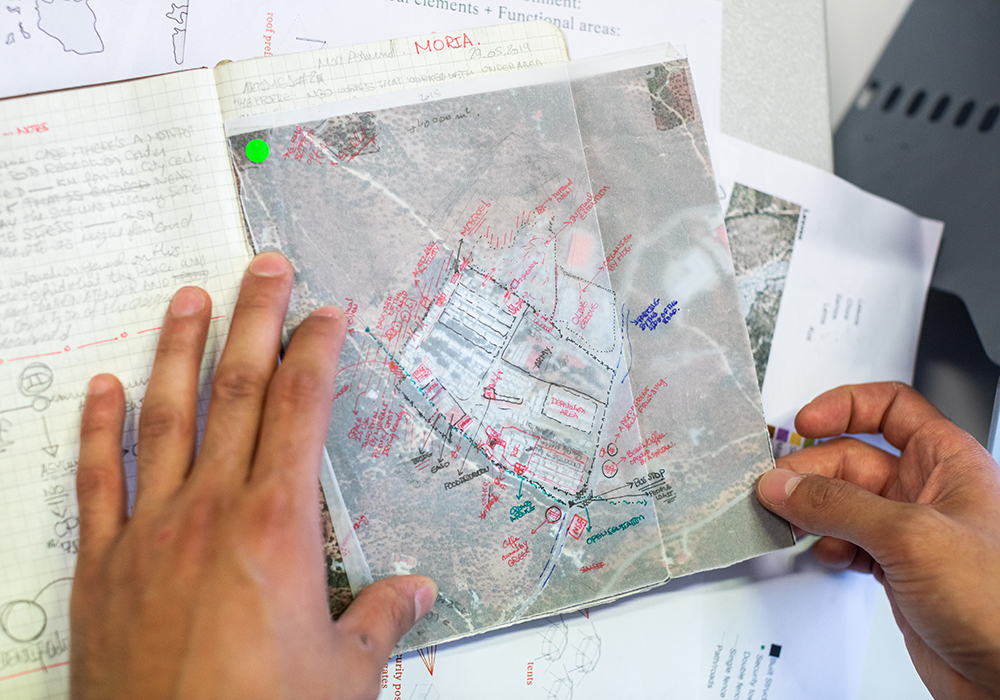

Alaa Dia is leaning over a satellite image. It depicts the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos before it burned down. He has laid a transparent film over the top of it on which he has marked the following: the areas where the refugees were registered, where the NGOs were stationed that offered the refugees help, where Frontex had its offices, and where the refugees were able to exit and reenter the camp through holes in the fence and avoid security – his aim was to understand who is doing what and where in those facilities.

“The markings on the transparent film supplement the satellite images, and together they provide a more realistic picture of the situation,” he explains. “Satellite images and maps don’t always tell the whole truth.” The 30-year-old architect has long worked with maps and the information they reveal or conceal. He also incorporates these insights into his teaching in the Critical Urbanism MA program, where he delves into the political and cultural aspects of cartography, emphasizing the power of maps - what they disclose and what they can hide.

Since 2019, he has been working on his dissertation in the field of Urban Studies, focusing on refugee reception centers and camps in the EU. He is examining five Greek islands in particular. “The Greek government essentially gave these islands up in order to protect the borders of the mainland: to detain people who dared to enter the EU informally and put them through the registration process that has nothing to do with care and everything to do with security, and if possible, to send them back to their homelands,” he says.

Focus on security, not care

With a master’s degree in architecture and a postgraduate master's in urban design, Dia is currently finalizing his PhD in Urban Studies. His focus: How the architecture of EU migration reception centers both reflects and impacts migration and border policies. “I aim to understand EU’s migration management strategy and its border regimes,” Dia expands. “These reception centers, although temporary in nature, respond to an enduring migration phenomenon - these prison-like facilities criminalize migration, detaining individuals until their lengthy admission process concludes. My research encompasses the humanitarian aid component and the security measures executed within these centers.”

For his research, he visited the Greek islands of Lesbos, Chios, Samos, Leros and Kos in 2019 and 2022 – and observed enormous changes in some cases. “I saw Moria in life and in death,” he says, referring to the fire that completely destroyed the reception center in 2020. During his second visit to Lesbos, he saw faces that were familiar to him from his first visit: “So the idea of it being a temporary stay doesn’t line up with reality,” Dia observes. The people who were forced to live in the islands and in those camps provided Dia with information that he would not have obtained from official sources about their way of living.

Alaa Dia grew up in Beirut, where he also completed his architectural studies. To this day, the architectural models and posters that he designed, drew, and built at different stages of his studies are still on display in his parents’ house in Beirut. But after finishing his master’s degree, it was Dia’s time to go beyond the borders of Lebanon. “I come from a country that is, in a sense, broken,” he says. He knew he had to leave to be able to get ahead. And he is not alone in this: “My sister lives in the USA and my brother lives in England. My parents travel constantly between Lebanon and the countries where their children live. I last saw my family in England.”

Language skills as a path to a dissertation project

He decided on Switzerland, where he completed his Master in Urban Design at ETH Zurich. He started his doctorate at the Department of Architecture. “I spent a year studying stones, but I found it rather boring,” he explains. He gave up his topic – stone-cutting technologies in modern history – and switched over to the University of Basel. “Here, Professor Cupers and Professor Ayata offered a project that captured my interest and identity much more intensively.” Cupers was looking for an architect who was interested in pursuing a PhD, and spoke French and Arabic fluently. Dia, who was educated at a bilingual Lycée, was a perfect fit.

For the project, “Infrastructure Space and the Future of Migration Management: The EU Hotspots in the Mediterranean Borderscape,” he was responsible for addressing the spatial and architectural components. For Dia, the interdisciplinarity of the project, which entailed a comprehensive and multi-sited investigation of migration management infrastructure across the five Mediterranean countries, Greece, Italy, Libya, Tunisia, and Turkey, was especially interesting.

Dissertation in its last stages

Dia’s shift from ETH’s architectural school to Urban Studies in the social science department at the University of Basel enabled him to adopt a more theoretical worldview. “My worldview expanded as I delved into this diverse realm, recognizing the interrelation of various disciplines," he says.

Alongside his work on his dissertation, Dia also teaches students in his own classes how to critically evaluate maps. “Teaching inspires me as it allows for the sharing of knowledge with students and helps me grow as an educator alongside them.”

When Alaa Dia submits his dissertation next year, he will have another border to cross. “My post-dissertation career aspirations lie in academia”, says Dia. However, there is no harm in thinking outside the box: “My architectural skills, coupled with my understanding of migration, borders, and humanitarian aid, might open up opportunities for consultancy or roles related to migration management or refugee-related topics.” But it certainly won’t come back to only being an architect: “I've moved past being intrigued by the only superficial layers of architecture or creating structures just for the sake of seeing my name attached to the buildings.”

In Focus: the University of Basel summer series

The In Focus series showcases young researchers who are playing an important role in furthering the university’s international reputation. Over the coming weeks, we will profile academics from different fields – a small representative sample of the 3,000+ doctoral students and postdocs at the University of Basel.