Social movements and the media.

Text: David Hermann

Political scientist and Middle East expert Ali Sonay from the University of Basel researches current events in Egypt, Morocco, Turkey and Tunisia – and the role played in them by the media.

From Casablanca to Ankara, from Twitter to the airwaves: A conversation with Ali Sonay is like taking a trip across North Africa and the entire Arab world all the way to Turkey, spanning the full breadth of contemporary and media history. The research associate on the Program of Middle Eastern Studies investigates patterns of social movements and the role of the media in the Middle East and North Africa.

For Sonay, it all started with the Arab Spring in Egypt in 2011, which followed the protests in Tunisia. At that time, he was immersed in the topic with his doctoral thesis: His interests lay primarily in the significance of networks in mobilizing and organizing the protests. According to Sonay, the April 6 Youth Movement was of crucial importance to the developments in Egypt. The movement’s origins can be traced back to a Facebook group created to support a workers’ strike back in 2008. After a short time, the group had the support of more than 70,000 people.

Digital mobilization

The Facebook group used the internet to mobilize parts of the population to take part in the protests against the regime of Hosni Mubarak. Sonay also highlights the role of cafes and streets as venues for people to meet and exchange views: “This is where the relationships and ideas that would later be disseminated via Facebook and Twitter were formed.”

Today, Sonay’s research receives a great deal of attention, as his focus on social movements represents a shift in traditional Middle East research. For years, security and the terrorist threat, extremism, fundamentalism and authoritarianism had been the dominant issues in the field, but after the events of the Arab Spring they receded into the background. This has led to a change in public perception: Today, even though much of the news coverage remains negative, the region is also associated with topics such as participation, diversity and democracy in public discourse, highlighting the ability of media coverage to create new realities.

Missing structures

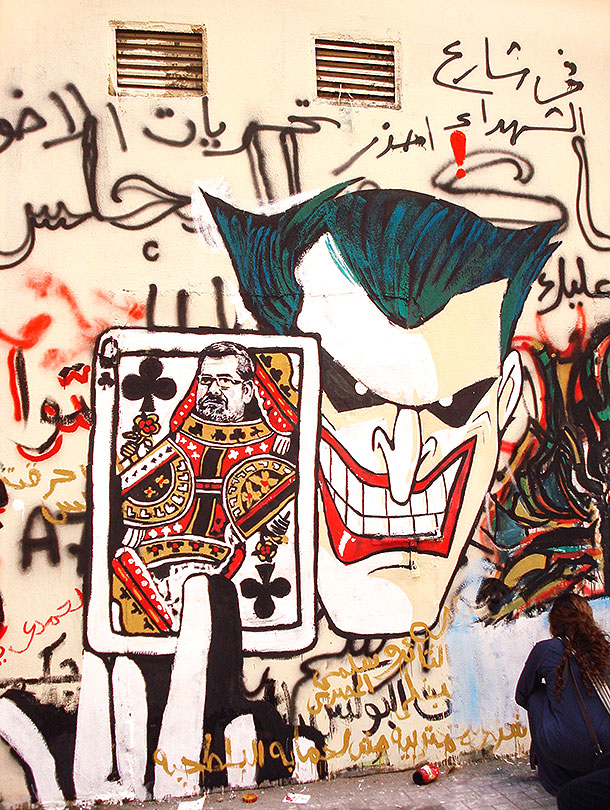

Eight years on from the Arab Spring, not much appears to have changed on the surface: Poverty and unemployment remain high. “The al-Sisi regime in Egypt currently in power suppresses independent media, especially online, and has enacted legislation mandating surveillance of large Facebook groups, for instance,” Sonay reports. Nevertheless, democratic awareness is on the rise, something the researcher views as cause for hope in the country: “Pluralism and participation were key values in the Arab Spring. It’s only a matter of time before the revolution is revived again.”

At the time, however, the movement did not have the necessary stability, Sonay says: “When a protest has such a broad range of goals as the April 6 Youth Movement, it often lacks the structures needed to become institutionalized. We see the same phenomenon in other social movements, too.” In Sonay’s view, the revolution in Egypt ultimately failed because the participants did not have a strategy for formal participation in the political process.

Different circumstances

As a postdoc at the University of Cambridge, Sonay studied contemporary media dynamics in Tunisia, Turkey and Morocco. He is keen to emphasize the value of a nuanced view of the Arab world. For example, it would be a mistake to draw conclusions about the entire region from events in Egypt, he warns. “Each country has its own economic, social and media environment, and social movements reflect this.”

In Morocco, he explains, the royal family is adept at anticipating social changes and reacting by appointing a new prime minister, for example. This allows the king to remain in the background, leaving politicians to deal with all the criticism. Despite its repressive system and severe limitations on press freedom, the country is considered stable, and enjoys a positive image. “Nevertheless, it hired an Italian surveillance company to weaken independent online media in the country with targeted attacks, for instance,” Sonay says.

The situation in Tunisia is slightly different: After the Jasmine Revolution of 2010 and 2011, numerous private media organizations were formed. Today, some of them are owned by leading economic figures with close ties to governing politicians. In spite of these connections, the media is considered relatively free. Public debate in the country is – as in the entire Arab world – heavily influenced by newspapers as well as radio and television broadcasters. A key element in this debate is the fear that the situation in Syria or Yemen could be replicated in Tunisia. The specter of these catastrophic alternatives is used to effectively silence critics of the state or government. These conflicts are also a recurring theme taken up by the transnational broadcasters Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera.

“Despite the turbulence of the region along with persistent unemployment and poverty, the country remains stable. This is the greatest success story to emerge from the events of 2011,” Sonay observes, adding that it is “a product of the broad-based democratic movement”: Unlike in Egypt, the overthrow of president Ben Ali was followed by the establishment of democratic structures involving large parts of civil society.

Media freedom under threat

As regards the fast-changing media landscape in Turkey, Sonay notes that “many independent media organizations have recently been bought up and taken over by government-friendly business leaders. As a result, reporting has become increasingly one-sided and limited to arguments tailored to their political base.” Even with the powerful corrective influence of the internet in the form of an active Twitter scene and a critical blogosphere, “anyone crossing certain red lines can expect to be the target of intimidation tactics.”

The Middle East expert has observed a decline in the value attached to truth, diversity and openness in the public sphere in Turkey, and draws a parallel between this trend in the Middle Eastern region and a global phenomenon: “Leaders who play fast and loose with the truth can also be seen in the US, Russia and China. This obviously gives governments in the region an additional sense of validation for their own authoritarian behavior.”

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.