Demographics and the labor market.

Text: Jörg Becher

What effect does an aging society have on the labor market? Instead of simply speculating, economics professor Conny Wunsch wants to deliver concrete answers – using a realistic model.

Barely any other phenomenon attracts as much controversial debate as demographic change: Is the Swiss economy at risk of a serious skills shortage as more and more “baby boomers” reach retirement age over the next ten or fifteen years? Or can we simply continue to offset the foreseeable decline in the number of working-age people with a greater influx of skilled workers from abroad?

This overlaps with the uncertainties of the debate surrounding digitalization: If cultural optimists are to be believed, the likely advances in technology and artificial intelligence will lead to an unprecedented boost in productivity, with huge improvements in efficiency and prosperity. At the same time, however, other voices are urgently warning that up to 50 percent of existing jobs could be swept away by the rising tide of digitalization.

Adaptation and change

Taken in isolation, such predictions – and especially the horror scenarios – are complete nonsense, says Conny Wunsch, Professor of Labor Economics at the University of Basel. “Experience shows that technological advances only cause temporary job losses. That’s because new job opportunities arise in parallel in other areas and compensate – or even overcompensate – for these losses. On top of that, most models completely ignore the ability of the labor supply to adapt to new circumstances,” says the economist, who specializes in labor market issues.

As Wunsch explains, it is not only workers’ ability to respond to shifting circumstances that is generally overlooked; current models of the impact of demographic change also fail to adequately consider changes in companies’ demand for labor. She says that, for practical reasons, labor demand is typically taken as a constant, although certain parameters such as wages, for example, can vary. Furthermore, many companies are able to adapt to changes in labor supply – for example, by providing targeted in-house training or by plugging the shortfall in skilled workers with staff of similar skill levels or from related occupational groups.

As part of a Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) project, Wunsch wants to shed more light on such issues and bring greater objectivity to these controversial debates. “I think it’s nonsensical to go for a one-size-fits-all approach,” she says: “You have to take as nuanced a view as possible of the effects, because different problems also require completely different solutions.”

Opposing developments

The researchers are initially focusing on developing a model of the domestic labor market that is as realistic as possible. It must not only take account of future demographic change but also reflect the interplay between labor supply and demand. The innovative aspects of the new model is that it accommodates dynamic adaptation mechanisms instead of excluding them from the outset. For example, these mechanisms include the effects of demographic change on product demand – senior citizens don’t buy the same products and services as twenty-year-olds – and their repercussions for the labor market.

Indeed, a number of sectors (healthcare or elderly care, for example) will see a significant increase in labor demand as a result of demographic change. And, because many of the newly created service jobs can neither be digitalized nor automated, the aging society will boost job opportunities in certain sectors of the economy. In the IT sector, too, there will be considerably greater demand for certain technology-oriented positions – such as those involved in support, maintenance, as well as updating equipment and systems.

Digitalization and the aging society are, for the most part, two opposing developments: Whereas demographic change causes part of the labor supply to fall away, digitalization has a moderating effect on labor demand. “In the end, the two effects might not be that strong,” says Wunsch, “because digitalization will offset some of the problems caused by demographic change.” As a result, instead of being a “job killer”, the wave of digitalization could turn out to be a benign mechanism that helps us cope with the threat of an aging society.

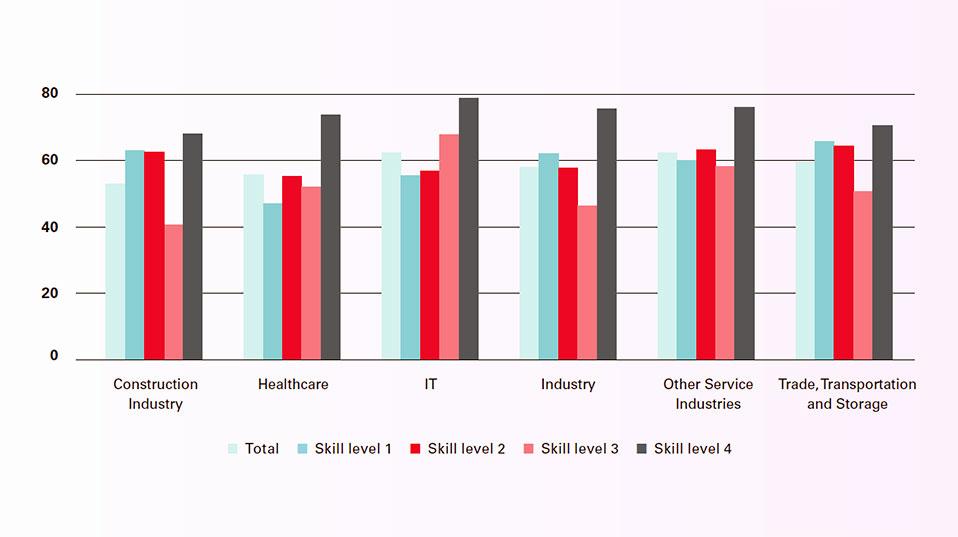

In developing a model that allows for dynamic feedback effects, so-called “substitution elasticities” play a significant role. These indicate how easily a person with certain professional skills can be replaced by someone of a lower skill level. Based on a company survey, the research group has now created an “affectedness index” that reflects this (see table): On a scale of 0 to 100, the table shows how strongly demographic change affects certain industry groups, which are broken down into four skill levels. The lower the value, the more strongly an industry group is affected.

Impact on construction and health

The initial analyses reveal significant differences: Demographic change has a particularly strong effect on skilled workers in construction (index value: 41), whereas the IT industry should have barely any trouble replacing workers at medium skill levels (index value: 68). In contrast, the IT sector is more likely to experience a shortfall in highly skilled specialists. Overall, the construction industry and healthcare are the worst affected; and the effect on the IT sector and other service industries appears to be significantly smaller.

Later in the project, the researchers plan to conduct a major survey of students at the University of Basel in order to address the current gaps in information for estimating the future labor supply: Do young people choose the “correct” occupations – in other words, those that will be sought-after by businesses in a few years’ time? Or do their educational endeavors fail to reflect the changing requirements of the labor market? “Instead of wildly speculating or making one-sided observations, we should finally take the opportunity to generate concrete knowledge,” says Wunsch.

Conny Wunsch is Professor of Labor Market Economics at the University of Basel. Her research focuses, among other things, on the effects of demographic change on the labor market.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.