Should Switzerland allow embryo donation?

Text: Irène Dietschi

In Switzerland, couples left with surplus embryos after IVF are not allowed to donate them to other infertile couples. Lawyer Valentina Christen-Zihlmann investigates whether this ban is still in keeping with the times.

If Valentina Christen-Zihlmann herself were to undergo IVF treatment, she would donate any surplus embryos to science. “I’m sure of this,” she says when we met at the café at Olten train station, “just as I’m sure that I’ll also donate my organs when I die.”

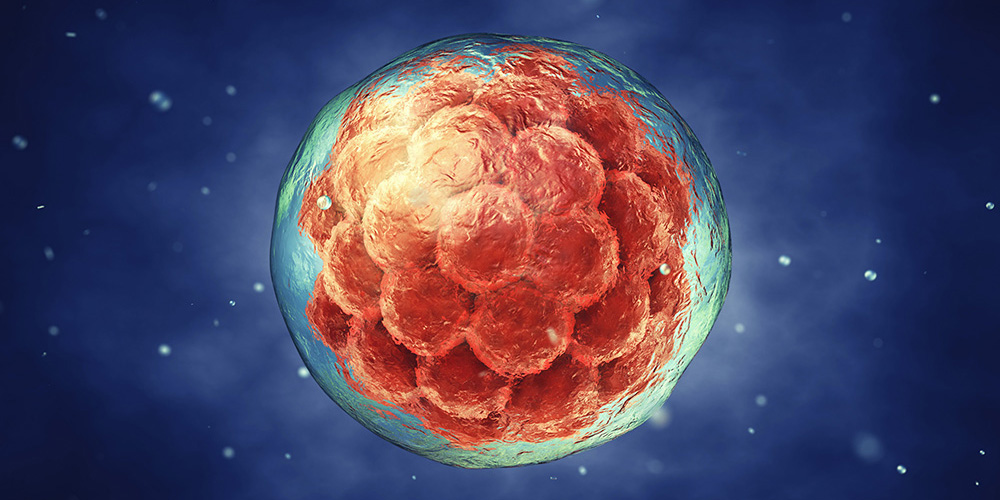

Surplus embryos are those cultured in a test tube during IVF treatment that are no longer needed for reproductive purposes — for instance, if a couple don’t want any more children or have separated. In Switzerland, couples who are left with these extra embryos can choose either to have them destroyed or donate them to scientific research, solely for human embryonic stem cell production.

From a reproductive medicine perspective, there is a third option: to donate the surplus embryos to another couple, who then “adopt” an embryo. In Switzerland, however, embryo donation is prohibited and any physician who violates this can face fines of up to 100,000 Swiss francs.

Valentina Christen-Zihlmann is writing her doctoral thesis at Basel University's Faculty of Law examining the reasons behind the ban and whether it can still be justified from a legal standpoint. The answer to the latter, Christen concludes, is a clear “no”.

New rules and their consequences.

Although for Christen herself, donating surplus embryos to another couple would be out of the question, she is clearly in favor of legalizing embryo donation. The lawyer takes a sip of her drink, leans forward, and explains: The ban on embryo donation runs counter to developments in legislation on reproductive medicine, including the parliament’s recent efforts to legalize egg donation, which is also banned in Switzerland. “However, the course was already set when the ‘rule of three’ was dropped for IVF.”

To give some background: In the early days, IVF regulations were very restrictive in Switzerland. A maximum of three embryos could be cultured and these had to be transferred to the woman’s uterus immediately. Embryo storage was banned. Since September 1, 2017, the rule of twelve has applied, meaning that twelve embryos can be produced per round of IVF treatment and that cryopreservation is now permitted. “In so doing, Switzerland has aligned itself with international IVF standards, which, by the way, takes a lot of pressure off the couples undergoing treatment,” Christen concludes. There is a big “but”, however: “The changes were not properly thought through at all,” she says.

This particularly concerns what to do with surplus embryos. The option of donating them to enable other couples to have children was something, according to Christen, that the legislators dismissed prematurely. “The argument was that embryo donation would recklessly encourage an increase in surplus embryos and this is something they wanted to avoid at all costs,” the lawyer explained. This was rooted in fears about IVF technology that have been around since the word go — around issues such as research abuse, selection according to specific criteria, and eugenics, for instance.

Something Christen says the politicians had failed to acknowledge, however, is that “it is the rule of twelve per se that results in more surplus embryos.” Introducing a regulation like this and permitting embryo storage, yet at the same time claiming that the aim is to “prevent surplus embryos” is contradictory.

Split Parenthood.

Although repeated motions to allow embryo donation have been submitted for consideration by the Swiss parliament, Christen explains that none have been successful. Each time, the ban is justified by citing the welfare of the child, which is said to be endangered when genetic, biological and social parenthood, especially motherhood, are separated.

But this argument does not hold water, either: “Studies on other countries have shown that the children involved suffer no psychological damage as a result.” Now the discussions on the introduction of egg donation also have to accept the notion of split parenthood, given that here, too, genetic and biological motherhood is separated. Of course, with embryos cultured in vitro using both donated eggs and sperm, parenthood is even more divided.

For Valentina Christen-Zihlmann, it is quite clear therefore that if Switzerland were to allow egg donation, “the legislature would have to address embryo donation, too – if only to draw a clear distinction between egg and embryo donation, a distinction that has so far often been absent.”

That said, Christen stresses that “the legal dimension is just one aspect — personal attitudes on the issue are another thing entirely.” Christen has spoken to couples who have had children with the help of IVF and no longer want any more but still have several cryopreserved embryos in storage in a laboratory.

In fact, there are cases where one parent is in favor of donating the surplus embryos to science, while the other is adamant that they would never allow “their own children” to be used as an object of scientific research. “This example demonstrates just how sensitive the issue is,” says Christen. Adding the option of embryo donation into the mix makes managing the situation even more complex. Christen emphasizes, however, that the decision about what should be done with the additional embryos should lie with the couple themselves.

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2023).