Embattled land.

Text: Olena Palko

For the first time since the end of World War II, military force has shifted borders on the European continent. What does the war in Ukraine mean for Europe?

On 18 March 2014, just two days after an illegitimate popular vote on the status of Crimea, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin confirmed the accession of the so-called Autonomous Republic of Crimea to the Russian Federation. Today, almost ten years later, experts believe that a military retake of Crimea by Ukraine is not possible.

Historical parallels.

Some media reports compared the international reaction to the annexation of Crimea to the policy of appeasement in the lead-up to World War II: Wishing to avoid war, Western powers allowed Hitler to expand German territory in the 1930s, which eventually enabled him to invade Poland. This attack developed into the deadliest military conflict in history, costing an estimated 70 to 85 million lives.

Similarly, the lukewarm international response to Russia's actions in 2014 paved the way for Putin to make further claims on Ukrainian territory. This undermined Ukraine's legitimacy both as a state and as a nation. In this context, Putin gave a speech on 21 February 2022 in which he implied that Ukraine was not a “real” country but rather a historical part of Russia. That same day, he signed a decree recognizing the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics as independent. In fact, he actually claimed the entire Luhansk and Donetsk regions, including those areas that continued to be controlled by the Ukrainian government. This decree was central to Putin’s initiating war three days later on 24 February 2022.

Just six months later, Putin proudly announced the incorporation of “four new regions of Russia”: in addition to Luhansk and Donetsk in the east, significant territories in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia in the south. At this point, Russia controlled about 20 percent of Ukrainian territory — an area equal in size to Switzerland and Austria combined.

Broken treaties.

Political and administrative borders between countries are based on international agreements, and their inviolability rests on a reciprocal pledge to respect each other's territorial integrity.

With its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has disregarded several international treaties and subsequently called into question their relevance. First, there are the Helsinki Accords of 1975, in which all participating states — including Russia and Ukraine as legal successors to the Soviet Union — agreed to “regard as inviolable all one another's frontiers” and to “refrain now and in the future from assaulting those frontiers.”

Furthermore, the signatories agreed to “respect the territorial integrity of each of the participating states” and to “likewise refrain from making each other's territory the object of military occupation.” These principles were reaffirmed in 1990 in the Charter of Paris for a New Europe after the Cold War. In the Budapest Memorandum of 1994, Ukraine agreed to surrender all its nuclear weapons to Russia on the condition that Russia, the USA, and the United Kingdom “reaffirm their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine.”

Unstable borders.

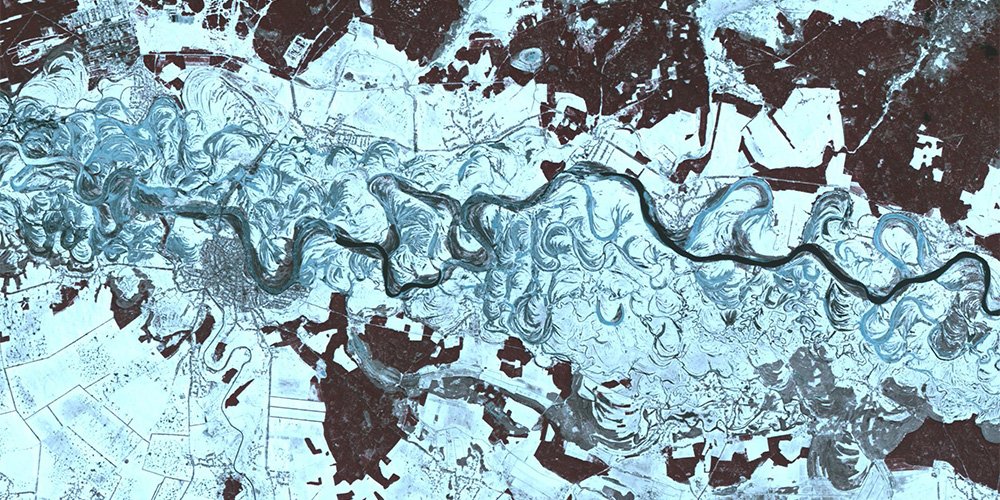

The current war also shows that, even in today’s age of globalization, freedom of movement, and mobility, undefined state borders can endanger a country's territorial and national security. While Ukraine's western border with Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania was precisely demarcated after World War II and has been strengthened since the European Union's eastward enlargements in 2004 and 2007, the borders in the northeast of the country were never defined exactly. The porous nature of the Russo-Ukrainian border was one of the reasons for the relative ease with which Russia was able to occupy Crimea and interfere in the affairs of eastern Ukraine. It has also allowed Russia to use these border regions as a base from which to launch air strikes on Ukrainian cities since late February 2022.

While some experts have tried to justify Russia's actions since the annexation of Crimea by looking to weaknesses in Ukrainian politics and identity, the history of Ukraine’s border-making provides no grounds to suggest that Russia's invasion of Ukraine was inevitable.

Rather, Russia's territorial expansionism reflects deep-rooted imperial fantasies within Russian society, whereby the boundaries of the so-called Russian world (“mir”) are determined by the reach of the Russian language and culture. As such, it can affect any state or people that happened to be part of the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union or have become part of Russia's sphere of interest. This has happened several times already: In addition to Ukraine, Russia has threatened the territorial integrity of the Republic of Moldova and Georgia and intervened in other regional territorial conflicts, as in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh.

By flouting international agreements, Russia has undermined the foundations of the continent's postwar order. Although Russia continues to commit well-documented war crimes, it retains its permanent membership and veto power in key international institutions, most notably the U.N. and its organs such as the U.N. Security Council and UNESCO. The fact that Russia is still able to use its seat to prevent any joint humanitarian response to the war-related plight of the Ukrainian people worldwide points to a major crisis in the international legal system.

This text was created in August 2023.

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2023).