Slow-growing bacteria respond more sensitively to their environment

Bacteria have a simple yet potent mechanism that controls their sensitivity to environmental stimuli. A new study by researchers at the University of Basel reveals that the responsiveness of cells is directly linked to their growth rate: the slower cells grow, the more sensitively they respond to their environment. This increased sensitivity can give the cells a crucial survival advantage.

08 May 2025 | Heike Sacher

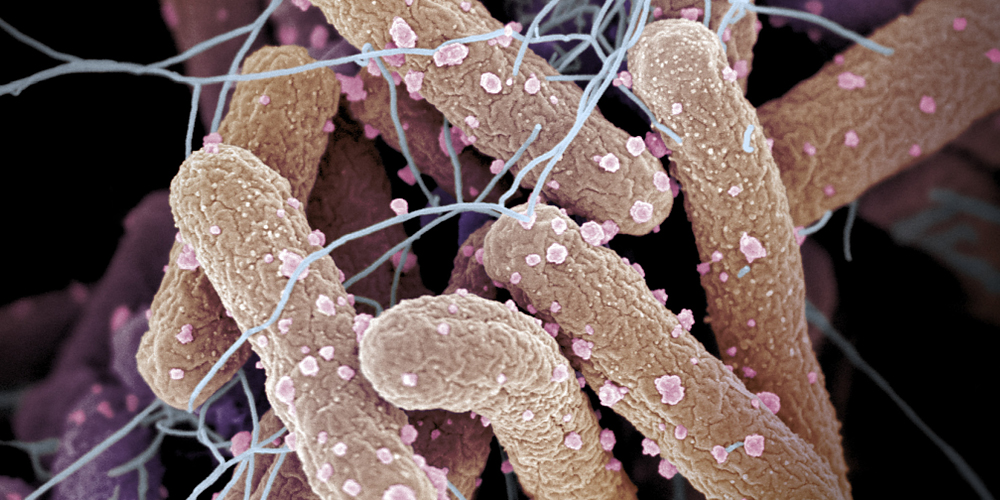

Researchers led by Professor Erik van Nimwegen at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, have discovered a new mechanism in bacteria that controls their response to prevailing environmental conditions. They derived their theory from a simple yet interesting observation: The growth rate of bacteria and their sensitivity to signaling molecules seem to be related. The research team subsequently demonstrated the underlying mechanism proposed by the theory in E. coli bacteria. The results of the study have now been published in Science Advances.

A simple and fascinating mechanism

“We discovered that the slower a cell grows, the more sensitively it responds to environmental signals,” explains first author Dr. Thomas Julou. “What particularly fascinated us is the simplicity of the mechanism and how generally it presumably occurs across biological systems.” When life is going well and cells are growing rapidly, they ignore the environmental "noise". When things are going badly, however, they "listen" very carefully, exploring the environment and deriving new survival strategies.

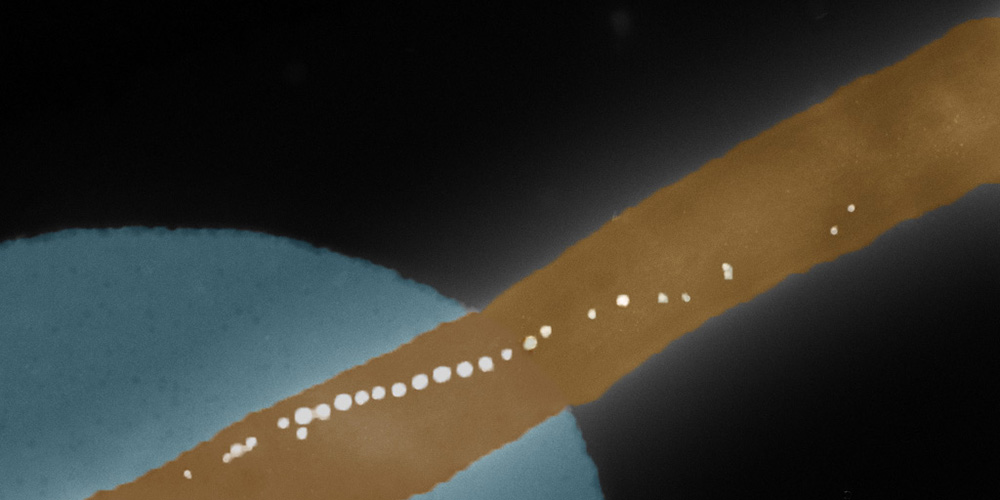

The underlying theory: The growth rate of a cell sets the rate at which signaling molecules within the cell are diluted, including those involved in gene regulation. In rapidly growing cells, signaling molecules disappear more quickly due to this dilution, so that external stimuli are damped and the cell effectively perceives them less strongly. In slow-growing cells, on the other hand, the signaling molecules persist longer and can accumulate more easily, making the cells more sensitive to environmental conditions.

Experiment with E. coli confirms theory

The research group was not only able to derive the existence of this effect theoretically, but also demonstrate it experimentally in E. coli bacteria. They used modern methods such as microfluidics in combination with time-lapse microscopy for single-cell analysis, but some results were also obtained using classical experiments that would have been possible even in the early days of molecular biology.

“For me personally, the study underscores that even simple biological principles that seem obvious in retrospect are sometimes only discovered through careful theoretical analysis,” states Erik van Nimwegen. The newly discovered link between cell growth and signal processing also provides new insights into the logic of cellular decision-making processes and has wide implications for understanding bacterial behavior including antibiotic resistance.

Original publication

Thomas Julou, Théo Gervais, Daan de Groot, Erik van Nimwegen

Growth rate controls the sensitivity of gene regulatory circuits

Science Advances (2025), doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adu9279