Macular degeneration: no cure in sight.

Text: Samanta Siegfried

Age-related macular degeneration is the most common cause of visual impairment in old age and is currently untreatable in the majority of cases. Researchers at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel (IOB) are investigating why this is such a complex disease.

For most of their lives, people needn’t give a second thought to age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The disease only affects three percent of the population just before retirement age, but this figure rises to one in three among those aged 75 or over. It is therefore regarded as the most common cause of visual impairment in old age – and the older the population gets, the more prevalent the condition becomes. Treatments are available. However, the prospect of a cure remains elusive to this day, despite the efforts of numerous researchers.

How can that be the case? Professor Christian Prunte, medical director of the Eye Clinic at University Hospital Basel, explains: “AMD occurs for a multitude of reasons, which are not yet fully understood. So far, it hasn’t been possible to define one central factor, but rather a variety of different risk factors. This complicates the course of disease significantly.” For example, the known risk factors include smoking, unhealthy eating habits and exposure to light – and research has shown that various genetic factors may also play a key role.

When tiles look warped

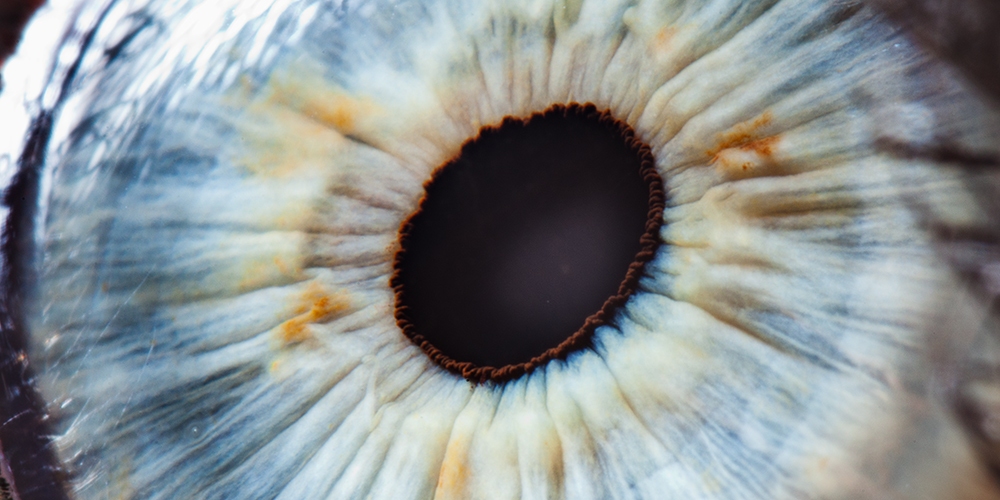

As its name suggests, the disease attacks the macula – an area at the very back of the eye that is also known as the “yellow spot”. This is responsible for the highacuity vision that allows us to recognize fine details. Although everything we look at directly is depicted there, patients usually only become aware of the disease’s effects at a relatively late stage. This is to do with the fact that the condition often only affects one eye initially, with the other eye compensating for any vision loss. In many cases, it is only when the disease crosses over to the second eye that patients complain of visual impairment. “Most people notice it while reading or because their vision is blurred when they look at people from a distance,” Prunte explains.

Yet, if AMD transitions to a wet form at a later stage of the disease, the patient experiences different effects: “In many cases, they can no longer perceive straight lines. For example, doorframes or tiles in the bathroom start to look warped.” The wet form causes swelling and deformation of the macula, which can lead to distorted vision and, in the worst cases, to blindness. Unlike the dry form, however, it only affects some ten percent of AMD sufferers. And, most importantly, it is treatable: If you inject a drug directly into the eye every few weeks, the loss of vision can be slowed down and sometimes even counteracted.

Underlying genetic defect remains unclear

Dry AMD, on the other hand, does not result in total blindness – although the loss of vision can be severe and may lead to considerable limitations in everyday life. To this day, this form presents a number of challenges for both physicians and researchers. Although there have been promising approaches that fared well in initial trials, Prunte says that “they didn’t prove sufficiently effective in the pivotal studies.”

Researchers at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel (IOB) are continuously testing new drugs, but they are also exploring approaches based on the principles of gene therapy. This involves using viral vectors to smuggle the corrected DNA into the cell where the defective gene resides in order to replace it.

Although promising gene therapy research is currently underway into another eye condition, known as Stargardt disease, the procedure for AMD is more complex: “The main problem is that, of all the patients studied so far, none have been found to exhibit a single genetic defect that triggers the disease,” says Prunte. “There are usually various genetic factors involved – and until you know which gene is responsible, you can’t replace it.”

Ultrasound with light

Another of the researchers studying age-related macular degeneration is Dr. Ghislaine Traber, a senior physician at the Eye Clinic in Basel. Like Prunte, Traber is responsible for clinical research – and she is currently involved in an observational study seeking to improve the assessment of disease progression. “There are many things we still don’t know, such as why the disease remains at an early stage in some AMD patients but moves to an advanced stage in others – or why the wet form appears in some patients as the disease progresses,” says Traber.

Known as the Pinnacle Study, this research project centers around an imaging technique based on so-called optical coherence tomography. This is vaguely comparable to an ultrasound scan, except that it uses light instead of sound to visualize the retina. Traber specializes in this field, having worked intensively on medical imaging of the eye and visual pathway at the Eye Clinic, University Hospital Zurich: “The layers of the retina are shown in high resolution, potentially revealing initial pathological processes in the early stages of AMD.”

One aim of the Pinnacle Study is to explore whether, even in the early stages, imaging can reveal certain retinal biomarkers that provide information about disease progression. In addition, patients will also undergo genetic testing in order to identify risk factors of disease progression. As well as the IOB in Basel, the study has participating centers in Europe and the USA. In total, 400 patients are to be recruited within a year and then observed over a period of three years.

Therapies are a long way off

At the Eye Clinic in Basel, 50 patients are to be incorporated into the study, all of whom must be aged over 55 and suffering from early-stage AMD. Once the Ethics Committee gives the green light, patient recruitment will begin. Summarizing the main objectives of the study, Traber says: “Knowing where the disease’s origins lie provides new insights for research and eventually also for potential therapies.”

For the time being, however, the ophthalmologist Christian Prunte offers little hope for those affected: “It will undoubtedly be a very long time before we find the first approaches to curing AMD.”

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.