The new me.

Text: Yvonne Vahlensieck

Trans people want those around them to be able to identify their true gender. Facial characteristics play an important role. Now, one Basel-based study is exploring whether it is possible to modify these characteristics without surgery.

A square jaw, a ridged browbone, a prominent nose. Studies show that even children rely on such characteristics to identify a person’s gender. “Evolution has trained us to identify even subtle differences to determine whether someone is a woman or a man,” says Alexander Lunger. “This happens mostly unconsciously.” Even the way in which light reflects off someone’s forehead and the intensity of that reflection influence the way we perceive gender.

Lunger is an attending physician for plastic, reconstructive and aesthetic surgery at the University Hospital Basel and a member of the team at the Gender Variance Innovation Focus treatment center. This center treats people with gender dysphoria/gender incongruence. Trans people often find it difficult to cope with the fact that their outward appearance does not match their gender identity. “There’s a conflict between their perceived gender and the gender that others assume them to be. We try to alleviate that suffering,” says Lunger. According to estimates, between 0.5 and three percent of people are trans. Many trans people decide to change their appearance, either by means of gender-affirming hormone therapy, genital surgery or either breast enhancement or mastectomy. Different people choose various treatments based on their individual needs.

Plastic surgery — an expensive undertaking

“For a long time, neither the community nor the medical establishment was fully aware of the importance of the face as a factor in the perception of gender,” says Lunger. “But of course it’s visible to everyone. It is the first thing to interact with the world around us.” Trans women often have difficulties fully concealing typical masculine characteristics such as a brow ridge, prominent jaw or receding hairline. Lunger speaks of trans women who are still identified as male in public despite their makeup, feminine hairstyles and women’s clothing. Such situations can be very challenging for those affected.

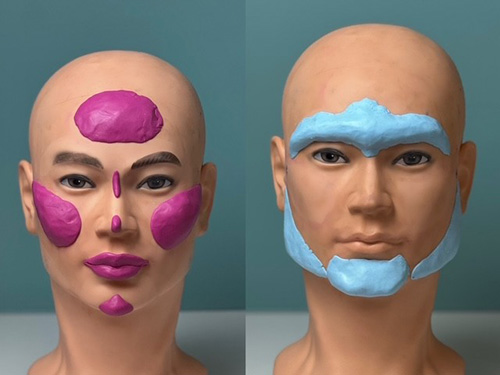

For this reason, many trans women — and some, but fewer, trans men — decide to undergo gender-affirming facial surgeries. In the case of trans women, facial feminization surgery can involve removing bone above the brow or along the jawline, reducing the size of a prominent nose or lowering the hairline. This helps trans people who wish for improved cis-passing to be more likely perceived as cis and experience less discrimination and aggression.

The problem with facial gender-affirming treatment is that this type of procedure is not regularly covered by health insurances in Switzerland (or most other countries). Many patients are simply unable to afford it on their own. Depending on what is involved, the cost of gender-affirming facial surgery can quickly add up to anywhere between CHF 20,000 and 60,000, says Lunger. Planning and performing these procedures is highly complex, requiring individualized digital planning with 3D-printed incision templates to ensure precision and safety while avoiding visible scarring. In Basel, this procedure always involves an interdisciplinary team.

Noninvasive option

For these reasons, Lunger is conducting a study to determine whether noninvasive facial attunement methods can be employed for gender dysphoria to achieve satisfactory results. His methods involve injecting botulinum toxin and hyaluronic acid filler. Put simply, the aim is to remodel the proportions of the face by adding volume — in contrast to surgical techniques, which tend to reduce volume. “These treatments are far more affordable than surgery and less risky,” says Lunger. Moreover, these techniques have been employed in aesthetic medicine for decades and have proven safe and effective.

The team intends to recruit 20 trans women and 20 trans men to participate in their study, known as FAITH (Face Attunement Injections Improving Transgender Health). Study participants must be over 18 years of age and have a confirmed diagnosis of gender dysphoria/gender incongruence. Nearly half of the target number of participants had received the noninvasive treatment by September 2025.

The study team records the effects of feminization or masculinization three and nine months later. The researchers use validated questionnaires to assess whether participants’ self-perception had improved. In addition, an AI uses photos of the participants for gender typing.

Safe to try out

In addition to the more affordable price tag, the noninvasive treatment has yet another benefit: It’s reversible. Botulinum toxin loses its effect after four to six months. Hyaluronic acid is absorbed by the body after a few months or years, or can be dissolved using an enzyme.

If the noninvasive treatment proves to have positive effects on participants’ dysphoria, it is set to become a recognized supplementary therapy option. It would be a suitable alternative for those who cannot afford surgery or are unable to undergo surgery for any reason.

“Trans people could try out an injection and see how it feels, so they could decide whether facial gender-affirming is the right option for them,” says Lunger. If they decide to pursue the noninvasive treatment, the injections of botulinum toxin and hyaluronic acid must be repeated on a regular basis.

Lunger emphasizes that the idea is not to make participants more “beautiful.” Before and after photos of his patients illustrate that the changes are subtle. Yet these minor attunements have a major effect on how patients’ genders are perceived by others. It is Lunger’s hope that if the study produces positive results, this will encourage insurance companies to cover the cost of facial attunement treatments as standard. In the long run, it could lead to significant savings on healthcare.

Studies on the effects of gender-affirming facial surgery illustrate that trans people generally experience an improvement in their quality of life following these procedures. Afterwards, they require fewer psychiatric sessions and take fewer antidepressants. “When people’s thoughts aren’t constantly focused on others’ perceptions of their gender, they have more time to concentrate on their careers and social lives,” says Lunger.

Alexander Lunger has been an attending physician at the University Hospital Basel since 2019. He founded the Facial Gender-Affirming Surgery unit at the Innovation Focus on Gender Variance. Lunger teaches at the Faculty of Medicine and engages in research projects focused on facial surgery .

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2025).