Linguistic detective work.

Text: Noëmi Kern

Until now, the history of Old Albanian has remained a mystery. A project at the University of Basel aims to change that. The search for linguistic clues also offers insights into social and cultural developments.

Albanian is a bit of an outlier. While most Balkan languages are Slavonic in origin, Albanian is a separate branch of Indo-European, from which most European languages are descended. Together with Greek and the Romance varieties, it is the only direct descendant of the languages widely spoken in the Balkans in Antiquity. Latin and Ancient Greek may be well documented and researched, but we still know relatively little about the Albanian language of the Roman Age.

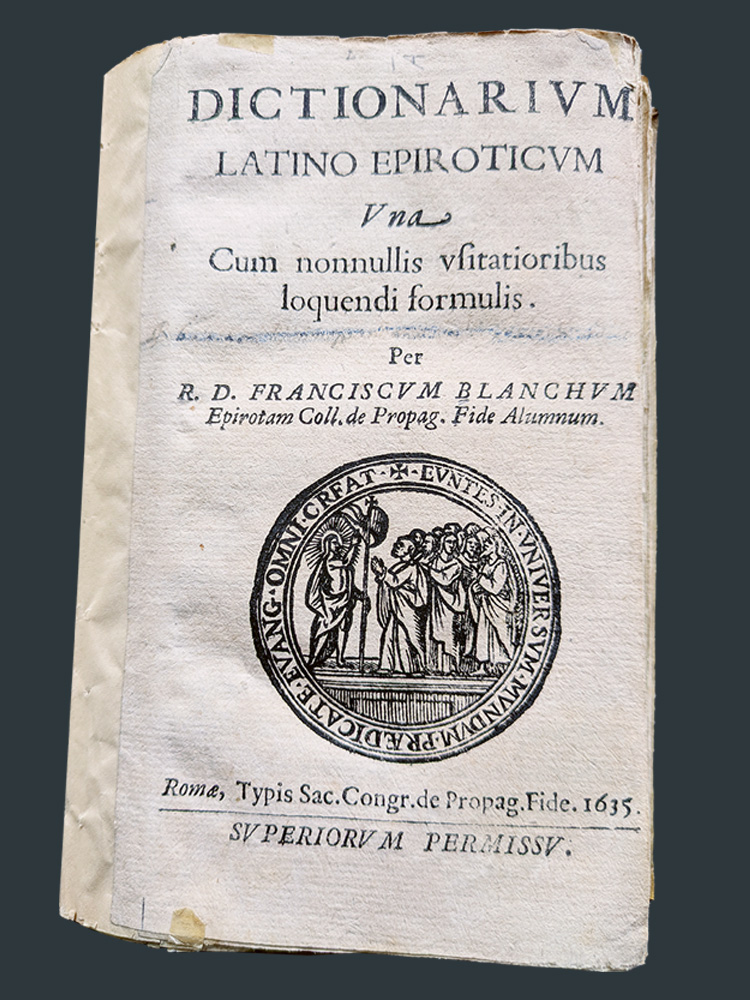

The problem lies in the sources: There are no pieces of writing in Albanian that show what the language looked like 1,500–2,000 years ago. The oldest known text in the Albanian language dates back to 1555. For comparison, Homer’s epics “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” are estimated to date back to the eighth or seventh century BC; and they are by no means the oldest Greek texts to have been handed down.

Most Old Albanian texts only came to the attention of academics in the 20th century, and even today, many have not been translated. “It’s only in the last two decades that a broader academic interest has developed in these texts and in the prehistory of the Albanian language, and the number of researchers working on the topic is small,” says Michiel de Vaan, a lecturer in historical and comparative linguistics in the Department of Ancient Civilizations, University of Basel. He leads “The Albanian Language in Antiquity,” a research project supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

It comes as no surprise that the earliest known texts are relatively recent: Well into the 19th century, the Albanian people were largely a society of shepherds and farmers with little opportunity for written literature. “So we don’t know exactly what the language looked like in Antiquity or the Middle Ages.” De Vaan aims to change this with his research, and to find out what Proto-Albanian looked like. “We can only do this indirectly by using linguistic reconstruction to trace the evolution of Albanian since the Roman Age,” he says.

As their starting point, he and his research group are using the aforementioned Old Albanian texts from the 16th century. The oldest known book, often called “Missal,” has a Christian background, containing prayers and Bible extracts from the Old and New Testaments translated into Albanian by a priest named Gjon Buzuku. “It isn’t a particularly exciting work of literature, but since we are very familiar with the original biblical texts, we know what the Old Albanian text is supposed to say,” de Vaan explains.

The bigger picture

Every language has a core vocabulary of frequent verbs, pronouns, body parts, kinship terms, etc. Many other words come from other languages; Old Albanian’s main source is Latin, as well as Ancient Greek, Slavonic and Turkish. These loanwords shed light on the regions to and from which people traveled and how different societies exchanged information. The closer the contact, the greater the linguistic influence.

Proto-Albanian has a particularly extensive lexicon of Ancient Greek and Latin words. “The loanwords from Ancient Greek tend to relate to trade, rather than the everyday mixing of cultures,” de Vaan explains. Latin is a different story: “In the first centuries of the Common Era, Latin was the most-spoken language in the northern Balkans. There’s so much overlap between the Latin and Proto-Albanian lexicon that many people must have been practically bilingual,” he states.

On the other hand, Proto-Albanian loanwords have been found in Early Romanian. Piece by piece, the researchers are getting closer to understanding this bygone language. This is also of interest to the social and cultural sciences. “Every language is a way of seeing the world. The words it contains indicate the encounters people had and how they spent their time,” says de Vaan. “So linguistic observations provide a better picture of what life was really like in the Balkans at that time.” Insights into Proto-Albanian are also relevant for Greek, Latin, Romance and Indo-European linguistics.

Tracking down patterns

In addition to vocabulary, the researchers are also comparing the grammar of Old Albanian to that of other Indo-European languages in this region. This allows them to identify patterns in how a language has changed. For example, very similar vowel systems with five to seven different vowels can be found in various languages spoken in the Balkans. German, English and French, meanwhile, have between 12 and 15 vowels. Word forms and verb conjugation also change over the years, revealing layers of linguistic evolution.

Researchers are attempting to reconstruct Proto-Albanian based on these phenomena. Despite all the evidence they have gathered, this remains a difficult task. Ultimately, nobody can prove what the language actually sounded like in Antiquity. Scholars can only make assumptions that cannot be verified due to the lack of written sources. “We still have a lot of questions. And while we can’t exactly solve them all, we welcome every new insight into the development of the language,” says de Vaan.

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2025).