Death is not the end.

Text: Christoph Dieffenbacher

Ancient Egyptian religion and culture were informed by the concepts of demise and renewal. Rituals provided stability and security in times of upheaval, for example at the end of life.

The same drama, every day and every night: In Ancient Egypt, the people believed that Ra, the sun god, traversed the sky each day in a barque before crossing the waters of the underworld by night. There, he had to slay the snake god of darkness and disorder in battle. Only then could Ra return to the sky to bring light and life to the world as morning dawned.

“Constant repetition and continuity were two of the core values of this advanced civilization,” says Sandrine Vuilleumier, an Egyptologist in the Department of Ancient Civilizations at the University of Basel. Even if divine enemies were destroyed, they didn’t really die — their continued existence would guarantee the continuation of the cycle.

This applied not just to the days, but also to the seasons: The annual summer flooding of the Nile was regularly awaited with hope and fear and celebrated as the start of a new year. The water was essential for agriculture throughout the Pharaonic kingdom — and therefore for the survival of its people.

As Vuilleumier explains, periods of transition and upheaval were considered uncertain and dangerous in Ancient Egypt. As the usual cycle was briefly halted, people would question what came next, what was going to happen, whether the world was about to end. In such situations, the solution was to perform rites and ceremonies offering stability and security.

Journey to the other side

Life and death were also part of an eternal cycle. “Death was not a definitive end, but rather the start of something new,” Vuilleumier explains. “People had to prepare in life for their later journey to the hereafter.” Several conditions also had to be met for a person to live on.

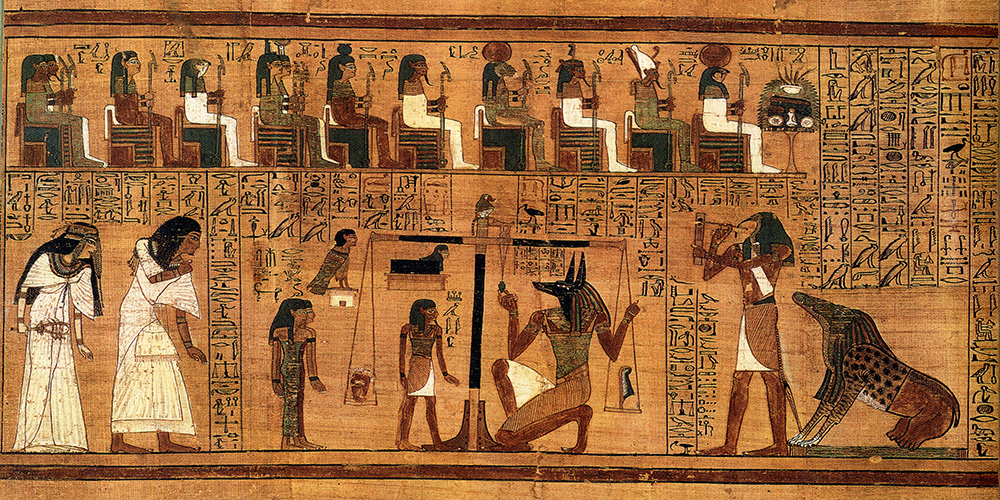

The deceased’s body had to be unscathed. And so, before it was interred, the intestines would be removed and the body would be dried with salt, mummified with balm and bandages and furnished with provisions and other grave goods. Next, the deceased had to place their heart on the scale before the court of Osiris, god of the dead. The heart had to be lighter than the feather of the goddess Ma’at. Only once the dead had passed this trial could they continue their journey to the other side. Here, there were fertile fields but, as Vuilleumier says, there were also monsters threatening: “Not everything was perfect on the other side.”

Spells and incantations

Vuilleumier specializes in funerary (burial) rituals in Graeco-Roman Ancient Egypt (around 300 B.C. to 200 A.D.). She translates and analyzes papyrus texts given to the dead to take to the grave: prayers, spells, incantations, instructions and even maps for the other side. These were supposed to aid and guide the deceased as they journeyed to an unknown realm.

“I rarely find myself with a shovel and trowel on excavation sites; I tend to use technological devices,” she says. Vuilleumier spends around two months of the year in Egypt, examining the colorful scenes and numerous hieroglyphs in a small temple in Deir el-Medina. She generally works with papyri in museums and archives and visits collections in other countries. Digitization and methods that employ artificial intelligence have made access to documentation much easier in many respects, although the original sources and their materiality must not be ignored.

It wasn’t just individual lives that underwent periods of change and upheaval; the politics of Ancient Egypt did, too. When a pharaoh died, elaborate coronation ceremonies and public festivals were organized for his or her successor: The new ruler wanted their reign to be a time of conquests, expeditions and majestic buildings, while still drawing on the notion of an idealized past.

Sunken desert city

Not everyone went along with this, however. Akhenaten and Nefertiti, a famous royal couple from around 1350 B.C., had no interest in this tradition, breaking radically with history and overthrowing the old divine regime. In Thebes (Luxor), then-capital of the Pharaonic kingdom, they abolished worship of Amun, the main deity, and proclaimed Aton to be his replacement. Even this wasn’t enough: The couple left the palace along with the entire court to establish the new capital, Achet-Aton (Amarna), in the desert.

“But this new beginning was only temporary,” explains Vuilleumier. Tutankhamun, the son of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, moved back to Thebes along with his court, reviving the previous deity. The city of Achet-Aton was abandoned and sank back into the sand. It was a good 3,000 years before archeologists happened upon the remains of the still-unfinished site — testifying to a beginning that came to an early end.

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2025).