Eyesight thanks to gene therapy.

Text: Yvonne Vahlensieck

Stargardt disease is a hereditary condition that leads to the loss of sharp vision at a young age. In Basel, scientists and clinicians are working together to develop a gene therapy treatment for the disease. The method is expected to be available for clinical trials within a few years.

The yellow spot on the retina, also known as the macula, measures just six millimeters across – and yet it plays an incredibly important role as the center of sharply focused vision. Without this, we would only see a blurred outline of our surroundings. “Sharp vision is something we rely on constantly, especially in modern society,” explains Professor Hendrik Scholl, Co-Director of the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel (IOB). “We use it to look at our cell phones, work on computers and recognize peoples’ faces in social interactions.” Retinal diseases that damage the macula therefore lead to a considerable reduction in quality of life.

A genetic defect with serious consequences

One such condition is the hereditary Stargardt disease, which typically has its onset in adolescence and quickly leads to the complete loss of visual acuity. Those affected retain some degree of mobility, but they can neither read nor make out detailed aspects of their surroundings. Although the disease is still considered incurable, that might be about to change: Scholl and his colleagues at the IOB are working on a gene therapy treatment aimed at halting the progressive loss of visual acuity and thereby preserving sharp vision.

The IOB chose Stargardt disease as one of its research focuses for several reasons: “Especially as this affects young people, it is a disease that deserves serious attention – even though it only occurs in one out of 8,000 individuals,” says Scholl, who also hopes that the findings from this project will lead to advances in the treatment of other, related diseases. For example, these include age-related macular degeneration, which affects around a fifth of people over 65 and, in industrialized nations, represents the most common cause of blindness in the elderly.

It is, furthermore, of great advantage that the genetic basis of Stargardt disease is well known. “Retinal diseases can be caused by mutations in many different genes and, so far, more than 200 of these genes have been identified,” says the geneticist Professor Carlo Rivolta, who was appointed professor at the IOB in 2019. “Stargardt disease, however, mainly results from mutations in only a single gene, the ABCA4 gene.” People who carry one defective and one intact copy of the gene are not affected. Only when a child receives a non-functioning copy from each parent will it develop the disease. Consequently, the mode of inheritance is recessive.

Targeted defect repair

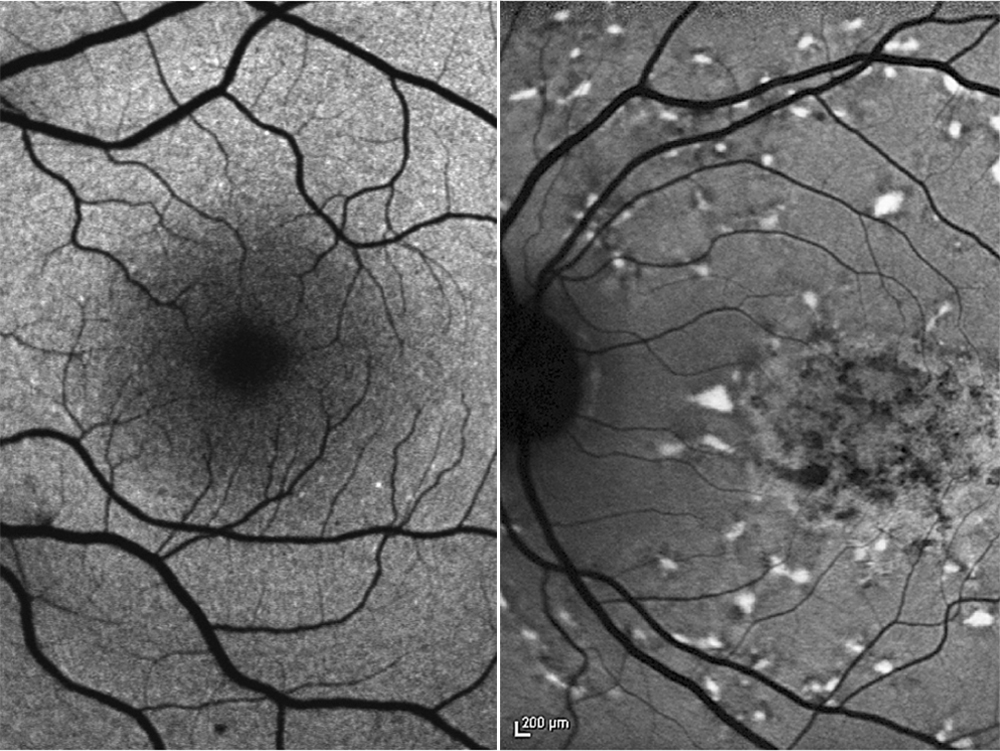

The function of the ABCA4 gene is also well known: It encodes a protein that removes the degradation products of Vitamin A produced during the visual process. If the retinal cells are unable to produce this transporter because of a gene defect, these degradation products accumulate underneath the retina and lead to damage to the macula. “In theory, it should be sufficient to restore the function of this single gene to achieve a positive effect,” explains Rivolta.

Therefore, the researchers are working on a way to correct the defective gene directly in the cells. They are trying to pack a nucleotide sequence that specifically recognizes the mutated site into a virus that is harmless to humans and then inject it directly under the retina of the patients. The virus transports the nucleotide sequence into the target cells. Enzymes coupled to the nucleotides are then directed to the mutated site where they activate cellular repair mechanisms that lead to the targeted correction of the defective gene.

A drug recently approved in the USA for the treatment of early childhood blindness demonstrates the potential of gene therapy in the treatment of diseases of the visual system. Furthermore, previous studies reveal that the effect of such therapies can last for many years – long-term observations of the patients treated will in time show whether the therapy lasts a lifetime.

Faster path from the laboratory to the hospital

Another goal of Professor Scholl is to accelerate the translation of basic science into clinical applications: The innovative methods developed by research groups at the IOB can contribute to this. For example, it is now possible to use tiny skin samples from patients to cultivate small cell clusters with a composition matching that of retinal tissue. These so-called “organoids” allow the scientists to test the gene therapy treatment in a petri dish. “This not only reduces the number of animal experiments, but also enables us to reach the stage of clinical trials faster,” says Scholl.

In parallel, other groups are analyzing the toxicity of this treatment and establishing methods of tracking its effects. At this rate of progress, Scholl believes that a clinical gene therapy trial for Stargardt disease could realistically start within the next five years, and he is already recruiting suitable patients from across Europe.

Yet, Scholl cautions against unduly high expectations: “Complete restoration of sharply focused vision almost certainly cannot be achieved using gene therapy, as many of the retinal cells are unfortunately damaged beyond repair.” Nevertheless, the researcher is optimistic that the treatment will yield substantial improvements in patients’ eyesight. And if this method proves successful, the distant future could see affected children receive preventive gene therapy at a young age in order to preserve visual function.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.