When a virus releases the immune brake: New evidence on the onset of multiple sclerosis

Autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis arise when the immune system turns against the body itself. Yet for most of them, it remains unclear why this process begins. Researchers have now identified how the Epstein-Barr virus can, under specific conditions, initiate early multiple sclerosis-like damage in the brain. This offers a new perspective on how rare immune events may shape disease risk.

13 January 2026 | Martina Konantz

There is mounting evidence that the Epstein-Barr virus may play a part in causing autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis. But one puzzle remains: almost everyone gets this virus early in life, yet only a few people ever go on to develop multiple sclerosis.

Now, a team led by Dr. Nicholas Sanderson and Professor Tobias Derfuss at the Department of Biomedicine of the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel, reports new evidence in Cell that helps resolve this puzzle. Working at the interface of clinical neurology and basic immunology, the researchers focused on B cells — a type of immune cell best known for producing antibodies.

A rare event in a highly sensitive place

Most people carry B cells that are potentially self-reactive, meaning they can recognize the body’s own proteins. Under normal conditions, this is not dangerous. When such cells encounter their target in the body’s tissues, they are briefly activated but then eliminated by strict immune safety mechanisms before they can cause harm.

The brain, however, is a uniquely sensitive environment. During infections or inflammation, B cells can temporarily enter the brain tissue. In most cases, this causes no lasting damage — but a coincidence of rare events can cause the safety mechanisms to fail.

When immune balance is disrupted

The current study shows that the Epstein–Barr virus can interfere with the normal control of B cells. One viral protein mimics a crucial “approval” signal that B cells usually require from other immune cells. As a result, self-reactive B cells can survive even when they should be shut down.

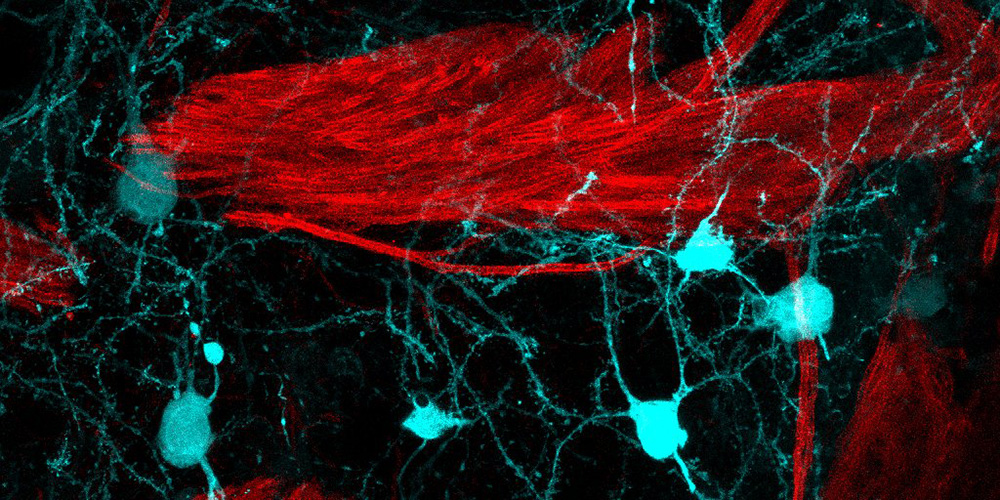

In experimental mouse models, these surviving B cells caused local damage to myelin — the insulating layer around nerve fibers — closely resembling early MS lesions. The process did not involve a widespread immune attack, but arose locally in the brain, shaped by a specific sequence of events.

“The role of EBV in MS has been quite mysterious for a long time. We have identified a series of events including EBV infection that has to happen in a clearly defined sequence to cause localized inflammation in the brain. While this is not fully explaining all aspects of MS, it might be the spark that ignites chronic inflammation in the brain,” says Tobias Derfuss, senior author of the paper.

One of several triggers for MS

Until now, B cells were thought to contribute to MS mainly through indirect mechanisms, such as influencing other immune cells. The new findings suggest that, rather than acting only indirectly, B cells may also play a direct role at the earliest stages of lesion formation. These new insights bring together several long-standing observations in MS research: the strong link to Epstein–Barr virus infection, the involvement of B cells, and the effectiveness of therapies that target them. At the same time, the researchers emphasize that this is not a single-cause explanation for MS. Instead, it describes one initiating pathway that could help explain why the disease begins — long before symptoms appear.

“Experts in the field mostly agree that both B cells and Epstein-Barr virus are somehow involved in the disease, but there is no consensus about how,” explains Nicholas Sanderson. “The model that emerges from the work of our team is very simple and therefore very persuasive. In a nutshell, we suggest that virus-infected B cells cause the lesions.”

By identifying a concrete biological mechanism at the very beginning of MS, the study shifts attention to the earliest moments when disease risk may still be shaped. Rather than focusing only on established inflammation, it highlights how timing, location, and immune history can determine whether damage occurs at all. This new understanding may help guide future strategies aimed not only at treating MS, but at preventing it. One possibility would be to tailor future vaccinations to prevent severe Epstein-Barr virus infections, and thereby reduce the invasion of the brain by out-of-control B cells.

Original publication

Hyein Kim & Mika Schneider et al.

Myelin antigen capture in the CNS by B cells expressing EBV latent membrane protein 1 leads to demyelinating lesion formation

Cell (2026), doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.12.031