How does the brain hear?

If you can't hear properly, you can't communicate properly. The cause of this problem does not always lie in the ear, but also in the brain. Neuroscientist Tania Barkat is therefore investigating how the brain processes sounds, and why this sometimes doesn't work out.

Even as a child, Tania Barkat always wanted to understand how things work. A future career in the natural sciences thus seemed a logical choice. After studying physical chemistry at EPF Lausanne, she finally found her true calling through her doctoral thesis in neurosciences. «After all, all humans wonder how perceptions and feelings develop in the brain,» Barkat says. «It's incredibly satisfying to find answers to such questions.»

After research stays at Harvard University in the U.S. and the University of Copenhagen, she became a tenure-track assistant professor of neurophysiology at the Department of Biomedicine at the University of Basel in 2015, and was promoted to associate professor in 2020. She is specializing in studying the so-called auditory brain because surprisingly little is known yet about how the brain perceives and processes sounds.

Concrete help for the hearing impaired

With her research, she ultimately wants to help the many people who suffer from malfunctions in the auditory brain. For example, the more than ten percent of the population, which is plagued by phantom sounds triggered by tinnitus.

Sometimes, the path from basic research to practical application can be very short - for example, when it comes to improving cochlear implants: such hearing prostheses stimulate the auditory nerve with electrical impulses and enable deaf people to hear, albeit with limited quality. Barkat and her team have now developed a mouse model for these implants, allowing her to see exactly how the different areas of the auditory brain respond to stimulation. Now she is working on optimizing the impulses, so that the brain cells are stimulated more precisely and at the same time the implant's battery lasts longer.

Basic understanding of nerve cell circuitry

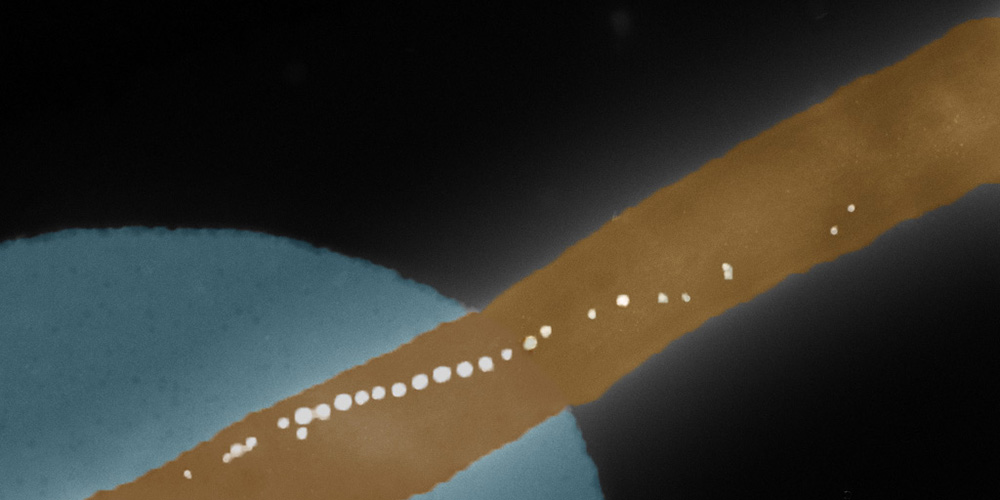

In addition to learning from this mouse model, Barkat uses a variety of other methods, including behavioral studies, computer simulations, as well as biochemical and molecular biology techniques such as optogenetics, in which certain brain cells are specifically switched on or off by colored light.

Recently, she has been able to identify two separate neural circuits in the auditory brain, each performing different auditory tasks. According to Barkat, such findings are important, even if they have no immediate practical application. A better understanding of the basic processes in the perception of sounds can ultimately help better understand hearing problems and prevent them from developing.

For example, in the early development of the auditory brain of a child there are several critical time windows: If an acoustic input is not received at the right time, this can later have consequences for auditory comprehension. Barkat is therefore now studying the mouse as an example to investigate how the circuits in the brain develop during infancy. Another project is devoted to the difference between active listening and passive listening to background noise, which may be one of the causes of attention disorders such as ADHD or autism.

Basel fosters the research spirit

Since moving from Copenhagen to Basel, Barkat has received substantial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (see box). So far, she has never regretted her move back to Switzerland. There are numerous outstanding neuroscience research groups in Basel - for example at the Friedrich Miescher Institute, the Biozentrum and the Department of Biomedicine - which form a unique research community supporting each other. «Of course, this also raises the standards you set for yourself», Barkat says.

In Basel, she also found an optimal work-life balance. Since she knows that her two small daughters are well looked after during the day, she can fully concentrate on her work: «You investigate the brain and suddenly you realize: ‘Oh, so that's how we hear’. Those are the moments that keep me going».

Function of nerve circuits during hearing

Tania Barkat heads the Brain & Sound Lab at the Department of Biomedicine at the University of Basel. The lab studies how acoustic stimuli are processed in the brain. The Swiss National Science Foundation is funding this research with around 1.3 million Swiss francs over five years, compensating for the Starting Grant from the European Research Council (ERC) that Tania Barkat lost when she moved from the University of Copenhagen to the University of Basel.